‘Fittest of rulers was he for a loud-mouthed, cackling land… This was his “policy” – turmoil and babble and causeless strife.’*

This is how Rudyard Kipling described Lord Ripon, the British Viceroy of India in the late 1800s. Now why would the writer of dreamy poetry and legendary animal stories that have enthralled children and adults alike for generations use such spiteful words? Because, the ‘gentle’ Kipling was at heart an imperialist. However, this story is not about Kipling, but about Ripon. Lord Ripon was a committed liberal and a champion of democracy. And for precisely that reason, he was vilified by his unworthy opponents.

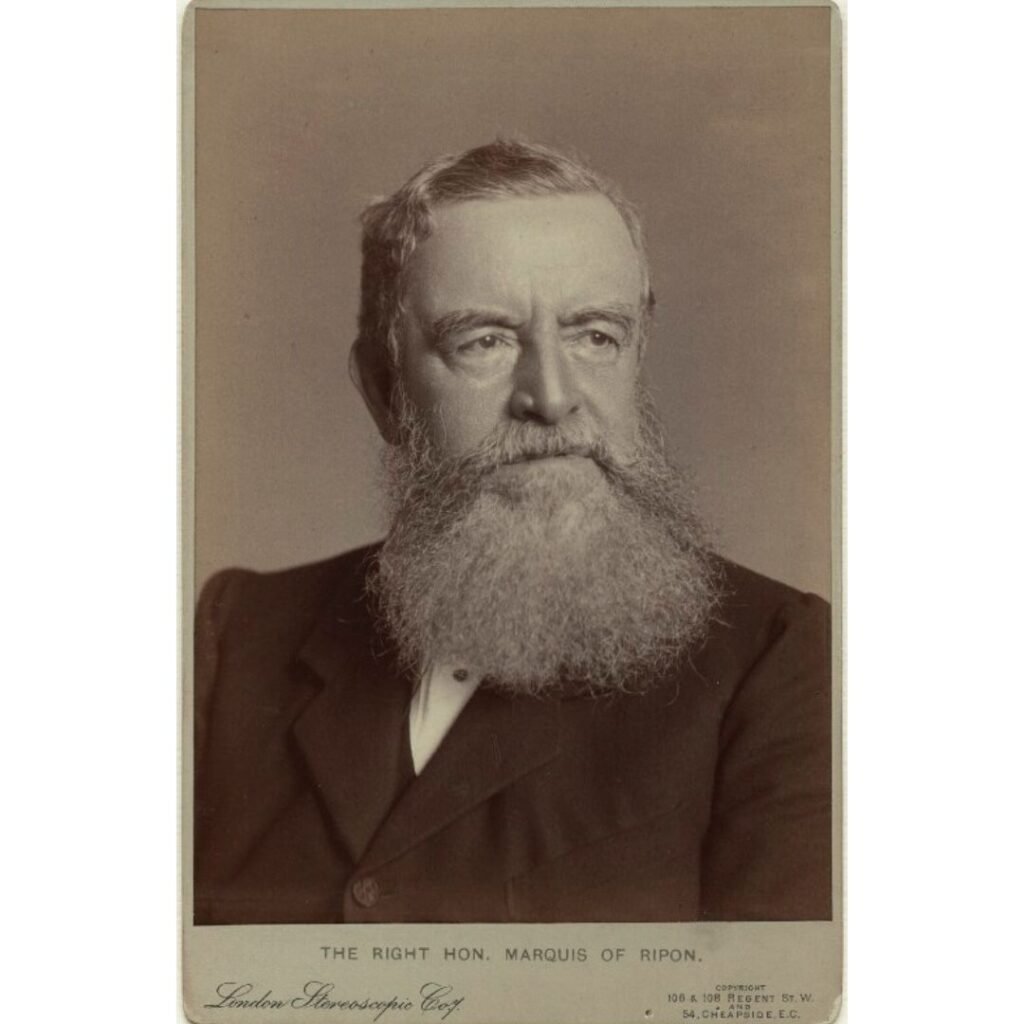

George Frederick Samuel Robinson, 1st Marquess of Ripon, was born in 1827, at 10, Downing Street, the official residence of the British prime minister. That was because his father was the serving prime minister. Ripon belonged to an aristocratic family. In fact, he was so privileged that he was not sent to school or college but was privately tutored. But for a person born into such privilege, he showed remarkable sensitivity to the poor and oppressed. So it was not surprising that he joined the Liberal party. Between 1858 and 1908, he held many important posts, including Secretary of State for War, First Lord of the Admiralty and more.

In 1880, the Liberal prime minister William Gladstone appointed Ripon as the Viceroy of India. Known as Gladstone’s man in India, Ripon was no stranger to the country. He had served as both Under-Secretary and Secretary of State for India. He arrived with a plan.

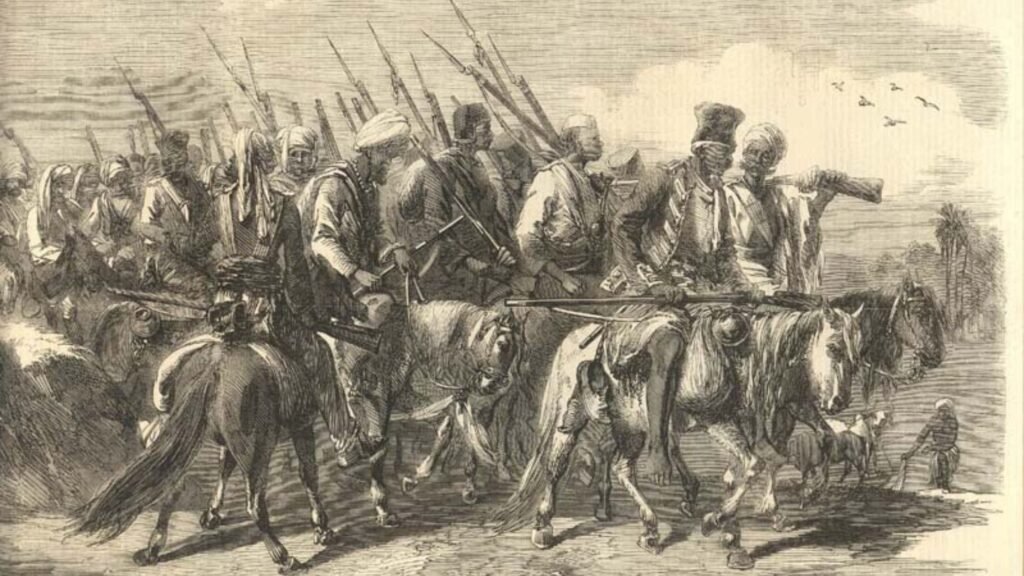

Ripon started with a disadvantage: he had inherited a war that hurt domestic growth. In 1878, Britain had pushed India into the Second Anglo-Afghan War. Now it had degenerated into a hopeless stalemate, draining the Indian government’s money and energies, with no possibility of any strategic benefit.

Ripon began a process of disengagement whereby the British troops would ‘honourably’ withdraw without much loss. This was a delicate operation, because during the war, Afghanistan had splintered into many warring regions. Barely 2 months after he assumed office, disaster struck. One powerful splinter group attacked and slaughtered British troops at Maiwand. The British troops were forced to retreat. The war hawks in England unfairly blamed Ripon. Randolph Churchill (Winston Churchill’s father) made it a cause celebre in the parliament, saying that the defeat was attributable not to the field commander (Brigadier Burrows) but to Ripon’s incompetent policies. Ripon weathered the storm and completed the honourable disengagement by 1881.

Ripon now turned his attention to domestic affairs. It had not even been 25 years since the First War of Independence, and there was a trust deficit between Indians and the British. Ripon’s predecessor, Lord Lytton, had worsened this by passing the Vernacular Press Act, which targeted the local Indian languages press. It was meant to suppress Indian criticism of the British policies in general and the Afghan War in particular. The government could easily shut down a press and confiscate equipment of non-English publications if they failed to comply. With the war behind him, Ripon repealed the Vernacular Press Act, and this won the hearts of Indians.

Although the Industrial Revolution had not percolated to India in a big way, its evils had somehow made their way to the country. Ripon was sensitive to the woes of the vulnerable working class. He passed the first ever Factories Act in 1881. It prohibited employing children below 7, reduced hours of work for children up to 12, ensured reasonable daily working hours with periodic rest breaks for all labourers and introduced safety procedures for machine workers. It was a very progressive legislation for those days. He reduced the salt taxes, because salt was such an important ingredient of people’s diet. Liberals like Florence Nightingale were his supporters, though it did not mean much in a British society dominated by Imperialists.

Detour: Read more about the British salt tax in our blog – The Great Wall of Thorns.

Ripon felt that Indians should have more say in governing their own land. He began delegating more power to local elected bodies. Many historians believe that Ripon was the ‘father of local self-government’ in India. Madras resonated with the slogan Ripon engal Appan (meaning ‘Ripon is our father’)!

Then came Ripon’s biggest move. In the British courts, everyone was supposedly equal in the eyes of the law. But it was a colonial myth. Actually, some people were more equal**. By the time Ripon took charge, qualified Indians – some of them learned jurists – were already serving as judges in High Courts. But there was a serious restriction on the jurisdiction of Indian magistrates and judges. If one of the defendants was European, only a British judge could preside over the court, even if an equally qualified native Indian judge was available. This was blatant racism.

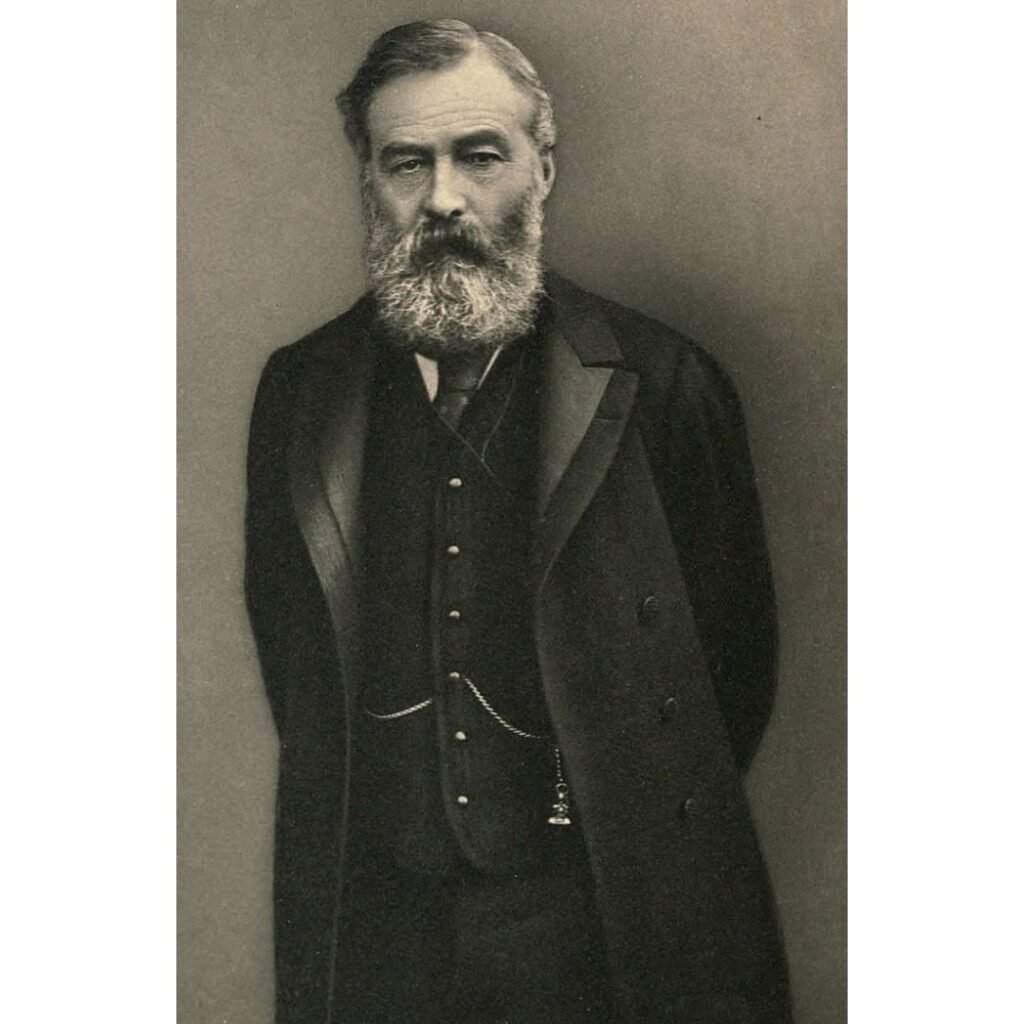

Now, Ripon saw the unfairness of it all. He appointed Sir Courtenay Ilbert, an excellent jurist and a humanitarian, as the Law Member of the Viceroy’s Council. With Ripon’s backing, he drafted the Ilbert Bill of 1883 which recommended equal power to Indian judges.

When it was tabled, it created an uproar. The British community in Calcutta (the Indian capital then), went berserk. Thousands of protesters took to the streets, carrying caricatures of Indian magistrates, calling them ‘wily snakes’ and other degrading names. Ilbert and Ripon were branded traitors to the nation and their effigies were burnt. The English papers in India and the British papers in England further stoked the racist fire.

The agitators achieved their aim of shocking the administration into relenting. After a series of negotiations, the amended bill was passed by the Indian (Imperial) Legislative Council in 1884. The original intention of the bill was severely compromised. In its new form, Indian magistrates could try European defendants, but the Europeans could easily bypass this process by demanding a special jury that was 50% European.

Ripon’s noble project was thwarted by vested interests. He saw no point in continuing, and resigned in 1884, a year before the end of his term. On the last day, he took a train from Calcutta to Bombay (the ship to England sailed from Bombay). Thousands of Indians lined up by the railway line and bowed silently to their hero. He had fought so hard, even antagonising his own countrymen, just for them!

Ripon’s exit was a turning point. Indian leaders now realised that the British were never serious about handing administrative power to Indians. It could be won only by taking the fight to the streets; the anti-Ilbert British protesters had just shown how it could be done.

Ripon’s legacy is still honoured in India. Thus, we have a town named Riponpet in Karnataka, a Ripon Street in Calcutta, and a Ripon Club in Bombay. There was even a Ripon Building in Multan, Pakistan (now called Jinnah Building). In 1913, the Madras Municipality opened its new building at Periamet, and named it after Ripon. The city corporation still functions out of this building. It came up three decades after Ripon resigned, when he was not even alive – yet his name was the obvious choice. After all, he was one of India’s greatest champions of local self-government.

Notes

1. *The introductory lines are from the poem ‘A Lost Leader’ by Rudyard Kipling in 1885. This anti-Ripon poem was soaked in vitriol.

2. **From Animal Farm by George Orwell: ‘all animals are equal, but some animals are more equal’. Orwell was an ex colonial police officer who resigned and became a great critic of British imperialism.

No comments:

Post a Comment