Independence notes: Different experiences in Portuguese Goa and British Malabar

At the stroke of midnight, the freedom finally arrived, largely with the efforts of the Congress. But what did this freedom mean to those who were neither ruled by the British, nor were they close enough to the Congress' political centre?

182

SHARES

- SHARE

Written by Adrija Roychowdhury | New Delhi | Updated: August 28, 2017 4:18 pm

Luis de Assis Correia (left) and M Madhavan (right) (Express Photo)

Luis de Assis Correia (left) and M Madhavan (right) (Express Photo)

RELATED NEWS

In the mid twentieth century, India’s struggle for freedom was at its peak, and leading the movement from the front was the Congress with a nationalistic fervour. Apart from the British rule in most parts of the country, there were regions which were controlled by other European powers like the Portuguese and the French.

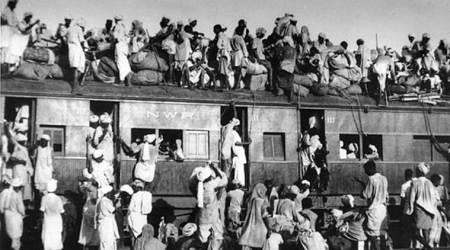

Also Read: Voices of Partition: One UP Muslim and two Pakistan born Hindus recollect the horrors of 1947

Amid the Congress’ freedom movement which involved a larger part of the country, there were a few regions which also saw a sudden rise in nationalist politics by parties against the Congress itself. At the stroke of midnight, the freedom finally arrived, largely with the efforts of the Congress. But what did this freedom mean to those who were neither ruled by the British, nor were they close enough to the Congress’ political centre? Far removed from the centre of Gandhian politics and the barbarity of Partition, how did the Independence of 1947 change their lives, if at all?

A Goan Catholic gives his story as we juxtapose it with the narrative from Malabar, a part of the British presidency of Madras.

Luis de Assis Correia: That time in Goa it was a criminal offence to even say ‘Jai Hind’

Luis de Assis Correia (Express Photo)

Luis de Assis Correia (Express Photo)

For the inhabitants of Goa, 1947 does in no way ring bells of freedom. Reeling under Portuguese governance until 1961, for the Goans the liberation of India from British rule was an experience far removed from what it was in other parts of the country. Luis de Assis Correia (89), currently a resident of Benaulim in Goa, grew up in a strict Catholic family and went on to join a student’s movement supportive of Subhash Chandra Bose. He recounts his days of living in Goa during the Indian independence movement and then later in Kenya when Goa got liberated.

“I am an old fossil born in Goa, Portuguese India. My birth certificate says that I am a Portuguese of Aryan race. That was the way the Portuguese described the inhabitants of their colonies. I grew up in a Catholic home. My mother was a very strict Catholic. When the World War II broke out my father was in the British Royal Navy based in Tuticorin and under the admiralty, order sailed from Calcutta to London and en route the ship was sunk by a german u-boat Off the coast of Ireland and my father was ‘killed in enemy action’

After my father’s death my family decided to send me to Madras for my education since the war had made things very unsafe. I did not know any English back then since my education was completely in Portuguese and Latin. My family arranged for a tutor to teach me English in Madras.

In Madras, I joined a students’ movement supportive of Subhash Chandra Bose’s INA. That was when I became familiar with the nationalist movement. But after Japan attacked Pearl Harbour and then moved to the Pacific, two bombs were hurled at the Madras harbour and our locality was declared a war zone. We were evacuated and stayed at a camp in Kudumbakam. They gave us Re. 1 as daily allowance and we would buy coconut water with that money since we could not tolerate the water they served us.

Four days later, our warden came and told me that I would be sent back to Goa through Bangalore. My relatives got me from Bangalore and in Goa I was admitted in class 4. This was 1943.

Four years later India attained Independence. That time in Goa it was a criminal offence to even say ‘Jai Hind’. Three days before August 15, absolute curfew was imposed in Goa. There was no electricity. The Portuguese government banned all kinds of celebrations. I had written a speech on the INA to read out in my school on August 15. The censor board passed it because they hardly knew anything about the INA. They just knew that the Japanese supported the INA and were happy that now Japan would take control from the British. Later, however, the police found out and stopped me from reading it aloud.

Because of the curfew in Goa, I got to learn all about Independence and Nehru’s take over and Partition only later from my friends in Bombay. As such though the Partition had no impact on Goa.

After Indian Independence, Portugal became absolutely anti-India. Nehru wanted Goa to be liberated from Portuguese control. He called Goa a ‘pimple on India’s face’. At that time I was completely against the Portuguese PM António de Oliveira Salazar. He had been a dictator for 28 years. He did not want us to get educated at all. Our life was always controlled and censored. We had no freedom of speech. Even wedding cards had to get cleared. We had to explain every day of our lives to someone or the other.

In 1958 I moved to Nairobi and I was involved in spreading among the Senior Kenya politicians – Tom Mboia, Oginga Odinga, Jmes Gichuru, Dr.,Julius Kiano and other politicians the light of goa under the yoke Of Salazarism.When Goa attained Independence in 1961 I was still in Kenya. We rejoiced there but I could not come home since I still held a Portuguese passport.

However, the liberation of Goa did not make me happy. The people who came to power, the so called freedom fighters, forced out all educated and competent Goans. Many of them have still not come back. The police and army were replaced by the Indian army. They forced their law on us. We all believed that life would improve after Independence. But once we were liberated, Nehru forgot all his promises.”

M. Madhavan: After Independence, as far as we were concerned there was no change in our lifestyle

M. Madhavan (Express Photo)

M. Madhavan (Express Photo)

Retired sports journalist M Madhavan was born in Kannur district which was part of the Madras Presidency back in the 1930s. He moved to Burma six to eight months after he was born as his father got a job in the Burma railways. He came back to Kannur on the eve of the Second World War in 1939, at a time when the fight for freedom was at its peak in India. He recounts his days when political protests had become the best excuse to bunk classes and the rise of the communist movement in the south, which he happened to join as a young school boy.

“I was seven or eight years old when my family came back from Burma. The fear of war was such that we had to come back. That was the time of the independence movement. I remember we used to boycott classes for a political movement if Nehru or Gandhi was arrested. People would go for hartals and we would simply get out of class and go home. I never went for the hartals, but it was a good way to avoid classes.

My family belonged to the landed community. We were not involved in any kind of political agitation. It is not that they supported the British. They just remained neutral. Only the Congress was agitating. Rest of the people were not organising any movement, neither did they know much. However, at home we did discuss Nehru and Gandhi and would be sympathetic towards their cause.

On August 15, we had a flag hoisting ceremony in school. People were very happy because most of the leaders who had been arrested were released that day.

My school authorities also suddenly turned nationalistic. Before independence, they would be very much against these agitations.

They were quite pro-British and would not allow us to go on hartals and all. However, after Independence they completely changed.

Though we knew about Partition, we did not discuss it much since we were not exactly affected by it. In my hometown, the relations between Hindus and Muslims were very firm. We did read about all the killings that were taking place in the North. People would talk about it and we would also read in the newspapers. We would also hear about Gandhiji’s satyagraha and many people getting beaten up by the police and still he was continuing, fighting for the cause of India.

During my school days, the Communist movement had just started taking shape and they were growing very strong. The Students Federation of India (SFI) was also coming up then. I was also part of it. But I never did anything apart from following them around. If they asked us to come out of class, we would do so. The SFI was very anti-British. Mostly they would carry out their movement underground. The police would be after them. When my father came to know about me becoming a part of SFI he told me not to go out of my way, or else I might get beaten up. But at that time I was very influenced by my friends and would go ahead with whatever they did.

After Independence, as far as we were concerned there was no change in our lifestyle. The governor of Madras exercised authority over my area. However, all his officials were Indians. So the British were barely present in our area even before Independence. For me the British were there somewhere, but I barely knew anything about them. After Independence, we naturally did not feel any difference. We just knew that we were independent now, ruling over ourselves.”

For all the latest Research News, download Indian Express App