David Cameron thanks keepers of Jallianwala Bagh memorial

AMRITSAR: For once, on Wednesday, Sukumar Mukherji, an austere looking man in-charge at the Jallianwala Bagh massacre site, looked content with his endeavour to preserve the massacre site.

"The 94-year-old wait has ended today. British PM David Cameron appeared apologetic for what our then colonial masters had done. There was remorse in his voice. The damage can't be undone but the British government's gesture is moving," said Mukherji.

"The 94-year-old wait has ended today. British PM David Cameron appeared apologetic for what our then colonial masters had done. There was remorse in his voice. The damage can't be undone but the British government's gesture is moving," said Mukherji.

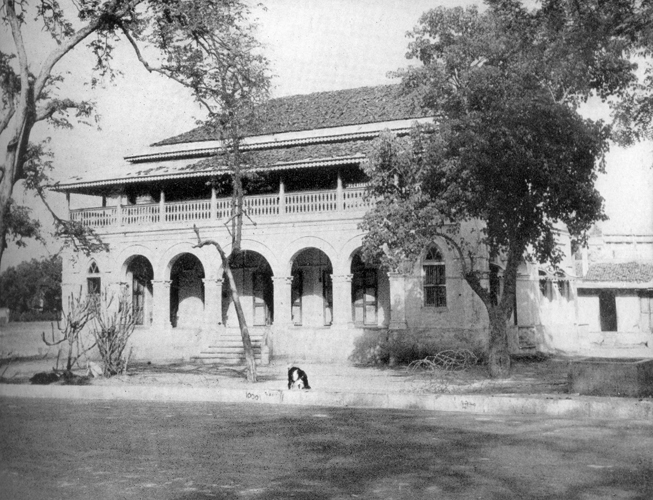

Ever since the carnage, the Mukherji family -- living in the crumbling,

falling-apart quarters of the massacre memorial -- has unflinchingly

guarded and preserved this poignant site through a trust.

Even on Wednesday, there wasn't much assistance from the state or central government either to facilitate the condolence visit. Mukherji had to himself arrange the wreath and bouquets of roses for Cameron.

In the company of suit-attired towering embassy officials from England, he walked in his modest cotton overalls and nattily worn rubber slippers.

"My eyes welled up with tears when Cameron praised the trust's effort to preserve the site," said an emotional Mukherji.

As TV crews mobbed him, he looked uncomfortable at the sudden attention. Thrice, he read out the note from the visitor's book aloud and then smiled at his daughter standing beside him.

"My grandfather had moved to Amritsar in 1910, from the Hooghly district of West Bengal. When the massacre took place, he was pained to see that no one cared to save the martrys' memories. He approached the Indian National Congress to pass a resolution to acquire the land and the trust was formed," Mukherji recalled, showing the 1920 land record.

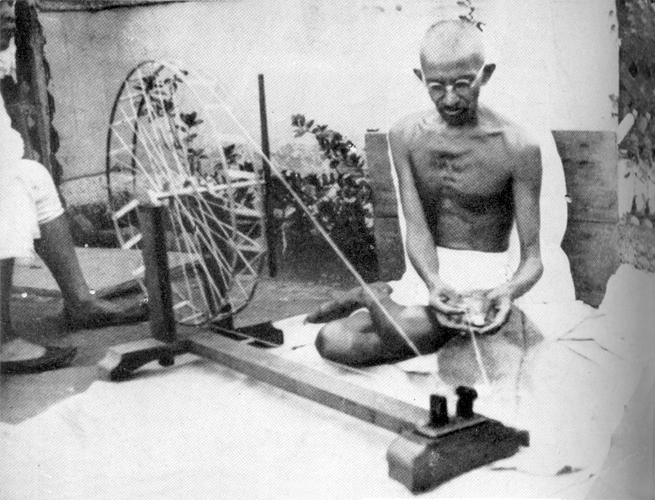

The land was purchased at a hiked up price of Rs 5.65 lakh in 1920, after Gandhi's appeal to the nation helped the trust collect the money. Mukherji's grandfather, Dr Shasthi Charan Mukherji, was appointed the first secretary of the trust, named the Jallianwla Bagh National Memorial Trust.

The museum has since continued to attract visitors and historians, giving the most palpable glimpse ever of the brutalities of the British Raj.

However, the family's own stay here has been ridden with poverty and a collective show of patriotism.

To preserve the heritage, the single room, for years has been shared between Mukherji's mother, wife and kids -- without the frills of a television set, air conditioner and decent lights. The members here still sleep on makeshift beds and cots, often in the company of pigeons and sparrows.

"We had rented a part of the building in 1974 to the Punjab National Bank to feed our family. We have survived on that," he said Mukherji.

The rent has increased only a trifle from Rs 11,500 to Rs 40,000 that barely fills the empty kitchens of the Mukherji family and the 14-member ancillary staff.

Even on Wednesday, there wasn't much assistance from the state or central government either to facilitate the condolence visit. Mukherji had to himself arrange the wreath and bouquets of roses for Cameron.

In the company of suit-attired towering embassy officials from England, he walked in his modest cotton overalls and nattily worn rubber slippers.

"My eyes welled up with tears when Cameron praised the trust's effort to preserve the site," said an emotional Mukherji.

As TV crews mobbed him, he looked uncomfortable at the sudden attention. Thrice, he read out the note from the visitor's book aloud and then smiled at his daughter standing beside him.

"My grandfather had moved to Amritsar in 1910, from the Hooghly district of West Bengal. When the massacre took place, he was pained to see that no one cared to save the martrys' memories. He approached the Indian National Congress to pass a resolution to acquire the land and the trust was formed," Mukherji recalled, showing the 1920 land record.

The land was purchased at a hiked up price of Rs 5.65 lakh in 1920, after Gandhi's appeal to the nation helped the trust collect the money. Mukherji's grandfather, Dr Shasthi Charan Mukherji, was appointed the first secretary of the trust, named the Jallianwla Bagh National Memorial Trust.

The museum has since continued to attract visitors and historians, giving the most palpable glimpse ever of the brutalities of the British Raj.

However, the family's own stay here has been ridden with poverty and a collective show of patriotism.

To preserve the heritage, the single room, for years has been shared between Mukherji's mother, wife and kids -- without the frills of a television set, air conditioner and decent lights. The members here still sleep on makeshift beds and cots, often in the company of pigeons and sparrows.

"We had rented a part of the building in 1974 to the Punjab National Bank to feed our family. We have survived on that," he said Mukherji.

The rent has increased only a trifle from Rs 11,500 to Rs 40,000 that barely fills the empty kitchens of the Mukherji family and the 14-member ancillary staff.

"I had proposed to the Central government the idea of introducing a nominal entry fee of Rs 2. However, that was dismissed by the Punjab government." he said.

Timeline: How Jallianwala Bagh Memorial came into existence

1919: Bengali freedom fighter Shasthi Charan Mukherji moves a draft for the trust

1920: Trust founded after a resolution passed by the Indian National Congress

1923: Land purchased after Gandhiji's appeal to the nation led to collection of Rs 5.35 lakh

1951: Jallianwala Bagh National Memorial Act passed by the government of India

1955: Design prepared by American architect Benjamin Polk

1961: President Rajendra Prasad inaugurated memorial on April 13, in the presence of Jawaharlal Nehru and other leaders

Grants given to Jallianwala Bagh Memorial

April 13, 1961 | Rs 10 lakh

May 2007 | Rs 22.98 lakh by PM Manmohan Singh

January 2009 | Rs 3.42 crore on sound and light show by ITDC

The JallianwalaBagh Massacre

The JallianwalaBagh massacre (also known as the Amritsar massacre), took place in the JallianwalaBagh public garden in the northern Indiancity of Amritsar on 13 April 1919. The shooting that took place was ordered by Brigadier-General Reginald E.H. Dyer.

On Sunday 13 April 1919, Dyer was convinced of a major insurrection and thus he banned all meetings. On hearing that a meeting of 15,000 to 20,000 people including women, senior citizen and children had assembled at JallianwalaBagh, Dyer went with fifty riflemen to a raised bank and ordered them to shoot at the crowd. Dyer kept the firing up till the ammunition supply was almost exhausted for about ten minutes with approximately 1,650 rounds fired. Official Government of India sources estimated that the fatalities were 379, with 1,100 wounded. The casualty number estimated by Indian National Congress was more than 1,500, with approximately 1,000 dead.

Dyer was removed from duty and forced to retire. He became a celebrated hero in Britain among people with connections to the British Raj. The massacre caused a reevaluation of the Army’s role in which the new policy became minimum force, and the Army was retrained and developed suitable tactics such as crowd control. Historians considered the episode as a decisive step towards the end of British rule in India.