The BJP Wants to Erase Nehru. Let's See What India Would Have Been Without Him

Trying

to erase Nehru’s imprint on the country is a tall order because he is

part of modern India’s DNA. Throw Nehru out of the equation and you end

up undermining India.

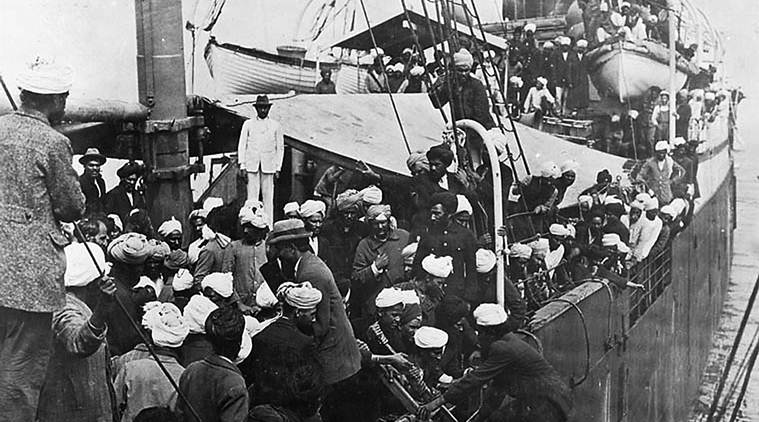

Nehru in a contemplative mood. Credit: Photo Division

Writing in the Sunday Times of India, Amulya Gopalakrishnan recently brought out the huge Nehru vilification industry that exists across cyberspace. In Rajasthan, India’s first prime minister is being wiped out from schools since it is more easy to fiddle with textbooks than write academic tomes based on verifiable facts, footnotes and peer-review.

But what would India have been minus Nehru ?

It is very difficult to separate one or the other of the towering individuals who fought for India’s freedom. But there are specific issues in which the personality of the leader played a distinct role. And so it is with Nehru. A counterfactual on India minus Nehru emerges from the consideration of the following eight points.

First, in 1927, he attended the Congress of Oppressed Nationalities in Brussels and gave the freedom movement an international outlook. His anti-imperialist cosmopolitanism certainly gave a modern patina to India’s freedom struggle.

Second, in 1928, Gandhi proposed dominion status for India, but Nehru is the one who demanded complete independence. In line with this, he opposed the Government of India Act of 1935, demanding a popularly chosen Constituent Assembly. Keeping with his views was the decision to move the historic Objectives Resolution of December 13, 1946 which categorically declared India’s decision to become an independent sovereign republic, notwithstanding the British desire to keep the country as a dominion.

Third, and this is perhaps the most intriguing example, in May 1947, Lord Mountbatten sent a plan for devolving power in India to the provinces – Bombay, Madras, UP, Bengal, etc. – allowing them to create confederations and only then transferring power. In other words, opening up the possibility of the emergence of several successor states in British India. This was the plan the British Cabinet approved and sent back to Mountbatten in May of 1947. On the eve of a meeting of Indian leaders announcing the plan, Mountbatten showed it to Nehru who was his house guest in Simla. Nehru was stunned and told Mountbatten that the Congress would under no circumstances accept this and wrote a long note to the Viceroy saying that this would be tantamount to the Balkanisation of India. Indeed, in this note he attacked a number of proposals, including one for the self-determination of Balochistan. Mountbatten postponed his announcement and, subsequently, the plan prepared by V.P. Menon to partition India and transfer power to two dominions was announced. There can be little doubt about Nehru’s role, detailed in Menon’s Transfer of Power, in compelling Mountbatten to stay his hand on a course that could have been disastrous for India.

Strengthening the Union

Fourth, as prime minister it was not possible for him to play a major role in drafting the Constitution, yet his chairmanship of the Union constitution committee and the Union powers committee was a crucial determinant in determining the balance between the powers of the states and the Union government which has managed to maintain the unity of this extremely diverse country. But there can be little doubt that his political outlook and philosophy, primarily his supreme faith in democracy, was reflected in the document which did not have to mention the word “secularism” to make its point because by making the individual citizen the focus of the constitution it bypassed the tangled issue of caste, community and religion.

Fifth, there are many who criticise Nehru for his handling of Jammu and Kashmir. What the critics don’t realise is that but for Nehru and his relationship with Sheikh Abdullah, at least till 1952, it would have been difficult to keep Kashmir in the Indian Union.

Sixth, he advocated the pattern of the economy which balanced the private and public sector. Indeed, this was in line with what Indian industrialists had put forward in the Bombay Plan. The critique of his socialistic leanings must be weighed against the fact that militant communism was the major opposition in the country, at least till the mid-1950s. By adopting a socialistic line, he helped encourage the split in the communist movement and outflanked their appeal.

Seventh, Nehru played a key role in passing four Hindu code bills which carried out the most progressive and far-reaching reform of the community. These had been originally mooted in the constituent assembly but were vehemently opposed by the conservatives and Hindu nationalists. Though the man behind the reform was a man who rejected Hinduism – B.R. Ambedkar – it was Nehru’s key support that ensured their passage in the first parliament. This modernisation, which removed the most oppressive aspects of Hindu society, was vehemently opposed by the RSS and its sister organisations. Among other things, the bills outlawed polygamy, enabled inter-caste marriages, simplified divorce procedures, placed daughters on the same footing as sons on the issue of inheritance of property.

Eighth, Nehru’s personal imprint is also visible in India’s nuclear and space programmes. The father of Indian nuclear science, Homi Bhabha, met Nehru on a voyage back from the UK in 1939 and began a life-long association. Nehru gave him the charge of India’s nuclear programme and he was answerable only to the prime minister. He actually piloted the Atomic Energy Act in the constituent assembly which gave rise to the Atomic Energy Commission chaired by the PM.

Negatives too

Of course, there are also negatives in the Nehru ledger. For example, sending the Kashmir issue to the UN, and his handling of the border dispute with China. Perhaps, minus Nehru, there might have been a different outcome, though it is not easy to discern what it could have been. However, on China it would most certainly not have been a military option. Nehru is on record asking General Cariappa whether India had the capacity to intervene in Tibet and he was told in writing that it was not possible given the weakness of the Indian military and the hostile terrain.

Another negative is the handling of the military itself. Nehru’s pacifist leanings and idealism made him a poor leader of the military. He allowed an important instrument of state power to run down and did not pay the kind of attention that was needed. And his final fault here was to overlook the impact of Krishna Menon’s abrasive personality on the military.

That said, it is clear that trying to erase Nehru’s imprint on the country is a tall order because he is part of modern India’s DNA. Throw Nehru out of the equation and you end up undermining India.

Manoj Joshi is a Distinguished Fellow, Observer Research Foundation.

ONE MORE POINT:-

Lifting of ban on RSS was unconditional - The Hindu

Oct 16, 2013 - On September 24, Golwalkar again wrote to Patel — also Nehru — demanding that the allegations and the ban be withdrawn because countrywide searches ... Refusing to leave Delhi, he asked the RSS workers to restart the ...

Sardar Patel banned RSS under pressure from Nehru: Advani - The ...

Aug 22, 2009 - He had pointed out that it was Patel who banned the RSS and put its ... only because Nehru asked him to, is slandering Patel, who was very ...

Aug 22, 2009 - But Advani ji pointed out that Patel banned the RSS because Nehru ... that his conscience did not allow just because Nehru wanted it done.

Nov 25, 2011 - The cover of the book titled Nehru-Patel: Agreement within Differences ... But Patel argued that they couldn't do so because of lack of concrete ...

Oct 31, 2018 - In fact, Patel, then the home minister of the country, wrote to RSS leaders in ... governments have always been anxious to allow reasonable scope for ... While Sardar Patel may have had a soft spot for the RSS before Gandhi's ...