Gandhi’s India and Beyond: Black Women’s Religious and Secular Internationalism, 1935–1952

African American women encountered Mohandas K. Gandhi in India in the 1930s and 1940s and influenced others whom they mentored to engage with nonviolence as a strategy both to liberate African Americans and to emancipate colonized peoples. Specifically, they advocated female empowerment in India and defined it as intrinsic to decolonization. Unlike African American male religious intellectuals who singularly engaged Gandhi about nonviolence, these black women internationalists created a discourse of solidarity with Indian women that expanded beyond their traditional activities of missionary activity in Africa. This shift away from race elevation to black women’s empowerment was the derivative effect of interactions in India between Gandhi and a cadre of African American religious intellectuals. These intellectuals believed that Gandhi’s successful deployment of nonviolent techniques in the fight against British colonialism had much to teach African American activists. Accompanying these scholars, Howard Thurman and William Stuart Nelson, in 1936 and 1946, respectively, were their wives, Sue Bailey Thurman and Blanche Wright Nelson. Though they heard Gandhi articulate his views about nonviolence, their takeaway from their sojourn in India was a sense of urgency for women’s empowerment in the Asian subcontinent and for harnessing the energy of African American women to support this project. Additionally, Sadie T. M. Alexander, though she traveled to India in 1952, discovered possibilities for cohesion between African American and Indian women. Alexander and other African American women who had been exposed to India envisaged themselves as activists in these interreligious and transnational contexts.1

African American religious intellectuals, all men, after meeting Gandhi in the 1930s and 1940s, developed principles and a praxis about nonviolence that influenced a succeeding generation of leaders and activists in the Civil Rights Movement in the 1950s and 1960s. Howard Thurman, who met Gandhi in 1936, understood nonviolence as a methodology as “some form of shock, by organizing a boycott or widespread non-cooperation.” Benjamin E. Mays reflected on his deep conversation in 1937 with Gandhi about nonviolence as “an active force” that must be practiced “in absolute love and without hate.” William Stuart Nelson credited Gandhi for “the persistent and wise employment of those instruments of power available to his people—mass organization, mass resistance, political solidarity, (and) economic leverage.” Nelson added that “the use of (these) pressures” required practitioners “to employ those pressures” in ways “not to hate, not to want to do injury, (and) not to destroy the possibility of reconciliation.” These Gandhian ideas, conveyed by these black male intellectuals, mainly through their overlapping affiliations with the School of Religion at Howard University, educated and energized students such as James Farmer and Kelly Miller Smith as well as other leaders in the civil rights struggle.2

African American women, especially in the historic black denominations, long had been involved in transatlantic ministries within the African Diaspora. The African Methodist Episcopal (AME) and African Methodist Episcopal Zion bodies established women’s missionary societies in 1874 and 1880, respectively. A second AME women’s missionary society started in 1893, and the Women’s Convention of the National Baptist Convention, USA, was founded in 1900. Women in the Church of God in Christ in 1911 and in the Colored Methodist Episcopal Church in 1918 followed with their own organizations. All inaugurated projects in the Caribbean and Africa. Though they often adopted the language of Western white missionary groups, they poured Pan-African meaning into what was superficially described as “a civilizing mission.” In Pittsburgh, for example, two AME women in 1894 founded the “first magazine published by the Woman’s Missionary Society.” Their masthead proclaimed “Woman’s Light and Love for Heathen Africa.” They belonged, however, to the Women’s Parent Mite Missionary Society, whose 1874 founding document linked them to AME founder Richard Allen and to the Haitian insurgent Toussaint L’Ouverture. Though we should rightly recoil from their use of the term “Heathen Africa,” it should not obscure their Pan-African consciousness and their support for ending European colonialism in Africa. They also endorsed an indigenization that showed familial cooperation with African women, who in pursuing common Pan-African objectives, functioned as full partners in pushing for continental self-determination. Charlotte Manye Maxeke, Amanda Mason, and Europa J. Randall, within a transatlantic religious body to which they and their African American “mothers” and “sisters” belonged, mobilized institutional resources to advance African autonomy.3

Maxeke, from South Africa, discovered the AME Church while a part of a singing troupe traveling in the United States. Because of financial hardships, a sympathetic pastor, Reverdy C. Ransom, arranged matriculation for Maxeke and others at the denomination’s flagship institution, Wilberforce University. Maxeke, exposed to such professors as the young W. E. B. Du Bois and the legendary African emigrationist and bishop Henry M. Turner, spearheaded a merger between the US-based AME Church and South Africa’s dissident Ethiopian Church that a family friend, M. M. Mokone, had founded in 1892. The Women’s Parent Mite Missionary Society (WPMMS) viewed Maxeke as a partner in strengthening a black religious presence in a region where white settlers had subjugated indigenous Africans. Hence, Maxeke, with a Wilberforce degree in hand, started a coeducational school in 1903 with a special emphasis on girls. She lamented, for example, that some African fathers “lashed” their daughters for wanting an education and preferred “to sell them for so many head of cattle,” a possible reference to a “bride price” or payment from the family of a potential bridegroom. “It would have made your heart ache to see their backs,” said Maxeke in a letter to her African American “mothers.” This familial relationship was reaffirmed in 1909 when the WPMMS planned a trip back to the United States for “our African daughter” to raise funds for the Wilberforce-Lillian Derrick School. Educator Maxeke, however, became increasingly politicized as South Africa’s white minority government intensified restrictions on the rights of indigenous tribes. In response, she joined a succession of organizations that fought these injustices, including the African National Congress and the Bantu Women’s League, an ANC affiliate. She fought the sexism espoused by settler whites and indigenous blacks.4

Just as Maxeke moved back and forth within the black Atlantic, Amanda Mason and Europa J. Randall forged Pan-African solidarity across national and colonial boundaries on the “mother” continent and resisted the hegemony of white settler and European power. Mason emulated Maxeke’s route through Wilberforce University and a partnership with African American women. She returned to her native Liberia to teach and then moved to the Girl’s School in Sierra Leone. When she married the physician-nationalist A. B. Xuma and joined him in South Africa in 1927, she became a leader in the WPMMS branch in that region. Tragically, Mason died in childbirth in 1934 at age 38. Europa Randall built an educational and congregational infrastructure for the AMEs through her diverse movements within West Africa. Born in Sierra Leone, Randall, in the 1930s, settled in the British-controlled Gold Coast and established a congregation in Essa Kado and several schools in the colony. Like Maxeke and Mason, Randall affirmed a peer cooperation with the WPMMS as a delegate to its 1939 convention in Chicago. These ties proved problematic for male clergy in the Gold Coast, because funding from these African American women provided her with an independence that they clearly eschewed. When Ghana gained its independence from Great Britain in 1957, Randall and other denominational officials agreed that the schools that she and others founded would be aligned with the educational system of the new African nation.5

This heritage and precedent of black women’s internationalism framed how other African American women pursued solidarity and empowerment for colonial peoples elsewhere in Africa and India. These church-based Pan-Africanists, however, differed from their India-focused successors. While Maxeke, Mason, and Randall drew funds from the religious organizations of African American women, travelers in India tapped into a network of interracial and international groups such as the YWCA and the American Friends Service Committee. Their alliance with these and other organizations facilitated their opposition to sundry structures of hegemony.

As important as the longevity of religious women in establishing Atlantic ties between the United States and Africa were leftist women who opposed white supremacist practices realized in global colonial and capitalist exploitation. A critical mass of African American women of diverse backgrounds both in the United States and the Caribbean affiliated during the 1930s with the Communist Party (CP). They were impressed with the CP because it aggressively addressed the devastating economic impact of the Great Depression on poor and working-class African Americans and the continuing racial injustices perpetrated against African Americans throughout the decade. Communist credibility in taking seriously the black struggle for racial equality persuaded crucial cadres of African American women to become leaders and operatives in the CP-sponsored League of Struggles for Negro Rights, the Unemployed Councils, and the International Labor Defense organization (ILD). The ILD, which vied with the NAACP to defend the Scottsboro Boys, attracted black women to CP efforts to exonerate the nine African American males who were wrongly accused of raping two white women in Alabama. One of the African American women activists, Audley Moore, formerly affiliated with Marcus Garvey’s Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA), credited the ILD with getting “a civil rights movement going.” Because the CP, like the UNIA, promoted black self-determination, Moore easily transferred her loyalties to the ILD. “If they’ve got a movement like that, and they’re conscious of this thing that Garvey had been speaking about,” Moore remarked, “then this may be a good thing for me to get in to help free my people.”6

Notwithstanding a de-emphasis on “respectability” as foundational to the activities and aspirations of middle-class black women involved in their own philanthropic, social, and religious organizations, their counterparts in the CP shared with them a heightened international consciousness. Each group of black women had an expansive awareness of parallels between the condition of African American women and that of other women in both colonized and socialist societies. As representatives of their African American club and denominational institutions, “respectable” women disbursed health and educational funds to and interacted with mostly colonized peoples in the Caribbean and Africa. Christine S. Smith, long active in the National Association of Colored Women’s Clubs, also served as president of the AME Church’s Women’s Parent Mite Missionary Society. In the late 1930s, Smith, the widow of an AME bishop, sailed to West Africa with the prelate of the jurisdiction and the denomination’s secretary of missions. They visited churches and schools, several of which Smith’s group financed, in Liberia, Sierra Leone, and the Gold Coast. Leftist African American women, during this same period, were similarly internationalist but mostly traveled to the Soviet Union.7

Most communist African American women congregated in Harlem and identified with the Soviet Union because of the stubborn persistence of American racism and what Erik S. McDuffie cited as the “search of the Soviet promise of a better society.” He added that “the Soviet Union served as a political terrain where black Communist women forged their ‘New Woman’ sensibility and a ‘black woman’s international’ that was committed to building transnational alliances with women from around the world.” Hermina Dumon Huiswold, a native of British Guiana, with her husband lived in the Soviet Union for three years starting in 1930. She matriculated at the Lenin Institute and learned both Russian and German. Her proficiency landed her a position as an interpreter at the school, where she engaged an international network of communist activists. For Huiswold, Maude White, Williana Burroughs, and other African American women, a Marxist-Leninist society without race and class distinctions and in which freedom for women seemed to be realized became a goal worth achieving in the United States. As a result of these experiences, leftist African American women, McDuffie argued, “challenged the bourgeois variants of respectability espoused by the church, Garveyites, and clubwomen” and envisaged “black women as a global vanguard” that deployed Marxist-Leninism to re-imagine their “collective identity.” These leftist interactions for African American women became foundational for the daring intellectual explorations of such thinkers as Claudia Jones. Jones, born in Trinidad and a journalist and theoretician for the black Atlantic, mobilized her Garveyite and communist sensibilities for regular contributions to the Daily Worker. She talked about the exploitation of the “overworked and underpaid black women” as deserving the targeted attention of serious radicals.8

The global alignments of leftist African American women were realized through their involvements in protests against the Italian invasion of Ethiopia in 1935 and in their support for the antifascists fighting for the republican government in the Spanish Civil War between 1936 and 1939. Both Claudia Jones and Esther Cooper, through communist connections to the Popular Front, became opponents of Italy’s attack on Ethiopia, one of two independent African nations. Louise Thomson, a founder of the Soviet Friendship Society and a member of the International Workers Order, shared with her Marxist associates the antipathies toward a fascist overthrow of Spain’s elected government. When Thompson went to Europe with the North American Committee to Aid Spanish Democracy, she included a three-week trip within Spain. She met Langston Hughes and other black intellectuals from the Americas, Moors who fought with Francisco Franco’s fascist forces, and African Americans who volunteered for the interracial Abraham Lincoln Brigade that supported the republican army. She interacted with Salaria Kee, an African American nurse working at a loyalist hospital near Madrid. Though Thompson was rooting for the triumph of democracy in Spain, she also hoped that a republican victory would weaken Franco’s ally, Italy’s dictator Benito Mussolini, whose grip on Ethiopia would be weakened. While in Spain, leftist African American women met international allies who shared with them a determination to aid both African American liberation and women’s emancipation. Such leftists as Claudia Jones challenged the “dominant definitions of black womanhood and the interconnected force of white supremacy and gender oppression.”9

Eslanda Robeson and Pauli Murray bridged the separate spheres of international activity that characterized African American women in club and denominational pursuits and those involved in leftist affiliations. Both groups intersected with a cadre of influential black women who emphasized ties to Indian women and viewed Gandhian nonviolence as an effective methodology to dismantle European colonialism. Robeson, wife of singer and actor Paul Robeson, emerged in the 1930s as a recognized writer and anthropologist in her own right. While living in London during her husband’s European performances, she met in Paris with Caribbean and African intellectuals. Also, she traveled within Africa, became a cofounder of the International Committee on African Affairs, and visited Spain to identify with the antifascists. Additionally, she nurtured leftist associations in the Soviet Union where she enrolled her son in a school that offered a “racist free education.” Moreover, her two brothers were Soviet residents, and one remained in Russia permanently.10

Robeson, notwithstanding these African and leftist associations, became intrigued with Gandhi and other anticolonialists in India. While both were in London in 1931, Robeson interviewed Gandhi, who in the previous year had led the Salt March to protest British taxation of this important commodity. This mass mobilization of 80,000 Indians was an unprecedented display of civil disobedience and a demonstration of widespread resistance to British hegemony. Gandhi, who came to Great Britain to lecture and mobilize support for Indian anticolonialism, recently had been released from an eight-month incarceration as a result of his insurgent activities. Robeson and Gandhi agreed that any defeat of white supremacy should yield equality for all peoples. Robeson’s biographer concluded that her meeting with Gandhi provided her with a better “understanding of colonialism” and broadened her “interest in India.” Her encounter with Gandhi also spurred a relationship with future Indian leaders Jawaharlal Nehru and Vijaya Lakshmi (Nan) Pandit, his sister, and sparked in Robeson “a lifelong interest in the cause of Indian freedom.”11

Unlike Robeson, Pauli Murray never met Gandhi but adopted his techniques toward protest against antiblack discrimination. In this pursuit, Murray was among the first African American activists to deploy Gandhian nonviolence in the black freedom struggle. In a strategy that resembled the Gandhi-led Salt March of 1930, A. Philip Randolph proposed in 1941 a mass mobilization of African Americans in a march on Washington to demand the end of antiblack discrimination in the nation’s defense industries. Before Randolph organized and popularized the March on Washington Movement, Murray had already adopted the use of Gandhi’s anticolonial methodologies in the emergent Civil Rights Movement. Murray read a newly published primer on Gandhian strategies, War without Violence: A Study of Gandhi’s Method and Its Accomplishments, a 1939 book by a Salt March participant, Krishnalal Shridharani. Murray unexpectedly applied these tactics in a 1940 bus segregation incident involving her and a female companion.12

After a series of shifting movements to find a comfortable seat for Murray’s ailing friend on a bus routed through Petersburg, Virginia, the two travelers landed unintentionally in the white section. Though the police and Murray seemingly defused the racially charged situation, the bus driver reignited the tensions with the black women. Police were summoned a second time, and Murray and her companion were arrested for “disorderly conduct” and jailed. The involvement of the local NAACP and eventually the national office and the Greyhound Bus Corporation escalated the incident and drew 200 observers to the courtroom where the case was being heard. With a Gandhian mind-set, Murray clarified the issue by shifting it away from the false “disorderly conduct” accusation to the actual and blatant case of racial discrimination. Also, the Gandhian principle of accepting jail without bail was operative in Murray’s response to the action against her and her friend. The judge upheld the charge of disturbing the peace and found them guilty. Moreover, another Virginia court sustained the ruling, increased the fine to a sum that the two could not pay, and returned them to jail until friends raised funds for their release. Like Gandhi, whose anticolonial protests included jail time, Murray came to envisage her activism as following this same trajectory. In 1947, she was motivated to support Bayard Rustin’s Journey of Reconciliation, sponsored by the Congress of Racial Equality, which featured nonviolent activists who tested laws like the one enforced in Petersburg that upheld segregation in interstate bus travel.13

Robeson and Murray, in connecting the distinguishable spheres in which leftist black women and their Gandhi-inspired counterparts operated, showed the solidarity between the two groups in eschewing Western white hegemony, whether expressed in racial hierarchy in the United States or in the overseas empire of Europe’s imperial powers. “Black radical internationalism,” a term that historian Barbara Ransby used to describe Louise Thompson, also applied to other leftist black women associated with the Communist Party. Because of a common outrage against racism and colonialism, Ransby’s nomenclature similarly characterized nonleftist African American women who advocated the use of Gandhian techniques for the black freedom struggle and explored strategies to achieve the elevation of African American and Indian women.14

Nico Slate in Colored Cosmopolitanism and Gerald Horne in The End of Empires have examined African Americans and Indians and their antiracist and anti-imperialist discourse from the nineteenth century into the post–World War II period. Slate borrowed W. E. B. Du Bois’s definition of “colored cosmopolitanism” as meaning “a united front against racism, imperialism, and other forms of oppression” from the “colored world” of African Americans, Indians, and others in the far-flung areas of Europe’s overseas possessions. Slate stressed the “interconnectedness of transnational social movements” that linked African Americans and Indians. Horne emphasized the “common experience of oppression to racism and imperialism” that African Americans and Indians encountered leading up to the declaration of India’s independence from Great Britain in 1947. The beneficial takeaway for African Americans lay in Indian anticolonialism as a part of the “larger anti-racist and anti-imperialist struggle that encompassed millions globally.”15

Slate’s and Horne’s studies, with their focus on global alliances among victims of racial and colonial oppression, describe an intellectual discourse that framed the attitudes and actions of nonleftist African American women who identified with the struggles of Indian women. Both groups benefited from their interactions with each other. African American women learned much about the complicated religious, political, and gender dynamics of Indian society. Indian women were similarly enlightened about the condition of African Americans and gained from the sundry services that African American women and their sponsoring organizations provided to them. African American women, who are mentioned by both Slate and Horne in their major discursive interventions, traveled to India from the 1930s through the 1950s, at a time when Gandhian nonviolence was mobilizing irresistible pressure against British colonial power. Anxious to harness this force to the African American freedom struggle, black religious intellectuals tried to learn first hand about Gandhi’s moral methodology of “soul force.” Moreover, African American women witnessed and participated in these exchanges but extended their focus to Indian women and how colonialism and the indigenous cultures affected them. What resulted were initiatives to sustain cross-cultural and religious interactions and to spearhead cooperative projects to end the racism and colonialism that afflicted both African American and Indian women.

Sue Bailey Thurman and her spouse, the prominent preacher and professor Howard Thurman, put African American religion into discourse with interfaith principles that affirmed black freedom objectives (fig. 1). Hence, Howard Thurman, impressed by Gandhi’s praxis of nonviolence as a liberatory tactic for subject peoples, aligned Christianity with the Hindu- and Jainist-derived concepts of satyagraha (soul force) and ahimsa (do no harm). The result was his 1949 classic, Jesus and the Disinherited, which portrayed an insurgent prophet of Jewish heritage who criticized Roman hegemony. African Americans, he believed, could draw upon diverse religious resources to mobilize against Jim Crow ideology and structures in the United States. Sue Bailey Thurman, fully on board with nonviolence, pressed Gandhi for specific advice for the African American freedom struggle. Beyond that, she drew from her India trip possibilities for concrete engagements between two groups of women who battled racism and colonialism in their respective societies.16

Sue Bailey Thurman (Sue Bailey Thurman Papers, Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center, Boston University).

Thurman, born in Arkansas in 1903, was the daughter and granddaughter of Baptist ministers. Her father, who served in the Arkansas legislature during Reconstruction, founded with Thurman’s mother the Southeast Baptist Academy in Dermott, Arkansas. Educated at Spelman and Oberlin, Thurman taught music at Hampton Institute, where she endorsed a student protest against a state law that forbade integration at a Hampton public facility. Before she became the second wife of the widowed Howard Thurman in 1932, she was an official in the YWCA.17

Already a professor and dean of Rankin Chapel at Howard University and a well-known lecturer and preacher, Howard Thurman accepted an invitation to travel in 1935 and 1936 to India, Ceylon, and Burma over four months on the Pilgrimage of Friendship. The International Student Christian Movement emerged in the 1910s out of the ecumenical and missionary initiatives of John Mott and others, most of whom were affiliated with the YMCA, who believed that youth were the best proponents for breaking down barriers of culture and prejudice among diverse peoples. Because of rising concerns over race, A. Ralla Ram of the Student Christian Movement of India, Burma, and Ceylon urged the organization of a black delegation to these populous Asian areas to promote conversations between peoples living within hegemonic Christian structures. Accompanying Thurman were Edward and Phenola Carroll and Sue Bailey Thurman. Going to India for Mrs. Thurman was hardly peculiar because Amanda Berry Smith, an AME evangelist, preached there in 1880 and Juliette Derricotte, whom she replaced at the YWCA, had gone to Mysore in 1928 to attend a Student Christian Movement meeting.18

The India itinerary for all four African Americans was full. Though Howard Thurman received the most invitations, approximately 135, both Phenola Carroll and Sue Bailey Thurman, respectively at 23 and 69 engagements, also lectured broadly to primarily female audiences. Carroll, the daughter of a Methodist Episcopal minister and a graduate of Morgan State College, spoke about poetry at a YWCA meeting and at the Woman Christian College in Calicut in southern India. Thurman spoke in Nagercoil on “Women’s Organizations,” in Ernakulam at a women’s meeting, at Alwaye at the High and Training School for Girls, and in Madras at the YWCA on “Social and Religious Forces in America.”19

When the Thurmans met Gandhi, the Indian leader asked them about African American history and to explain why the slave forebears of African Americans preferred Christianity over Islam. Muslims, if they were slaves, Gandhi said, retained religious equality with their masters, while the same seemed untrue in Christianity. White Protestant and Catholic slave owners, notwithstanding black conversions and access to church sacraments, preserved the chattel status of their slaves. Islamic societies generally eschewed this definition of slavery. With time winding down, “Sue asked, with a tone of urgency, under what circumstances Gandhi would come to America as the guest of Afro-Americans.” She queried whether he would come “especially to the Black community of the South, where this [nonviolence] would be put into practice?” Gandhi demurred because the effects of colonialism, he declared, had caused Indians to lose self-respect. Moreover, untouchability had to be addressed and the divisions between Muslims and Hindus needed to be healed. That these interreligious tensions led to a partition of India and Pakistan accompanied by widespread violence, despite Gandhi’s efforts at reconciliation, became for him a source of profound regret. This failure at transcending these religious differences contributed to Gandhi’s assassination in 1948 by a fellow Hindu. Though he would not come to the United States until these issues were resolved, Gandhi expected that through “Afro-Americans … the unadulterated message of nonviolence would be delivered to all men.”20

Sue Bailey Thurman left India with a reawakening about Gandhi and his emulation of Jesus. Gandhi, she said, was “a high caste,” but “he looked upon Jesus as one of those suffering souls who had given his life.” As she and her husband sang with the Indian leader “Were You There When They Crucified My Lord?,” Gandhi believed these lyrics “represented the deepest meaning of sacrifice in the human spirit.” She commended Gandhi because he “became as poor as the poorest in order to keep this sympathy with their point of view.” Thurman was reinforced in her belief in nonviolence after a visit to the Tagore Institute, which paid tribute to the poet Rabindranath Tagore. “Black people,” she said in reflecting on his poetry, “might save America without violence if we had sensitivity enough to live above or transcend the world of prejudice.”21

Sue Bailey Thurman returned from India convinced that African American women, while historic heroines in the black freedom struggle, should now move with greater vigor into the international sphere. Despite a history of black women’s internationalism, principally in the religious realm, these moral impulses needed to be more overtly political and targeted against racial and colonial hegemony. In 1941 Thurman, in “The Negro Woman in the Present World Crisis,” a speech given before a black women’s club in Alabama, praised Harriet Tubman as “the greatest emancipator [who] delivered 400 of her fellow slaves to freedom in the North” and Sojourner Truth, “who helped to win suffrage for all women as well as fight for abolition.” In another speech, Thurman noted that this nineteenth-century heritage showed that black women embraced the role of “defender [and] the source of protection of minority groups and good causes involving the fight to give freedom to all those for whom it is denied.” Nonetheless, Thurman announced a new “battle area” and “a spiritual duty” that required African American women “to improve life at the level of all people and especially the humbled, distressed and persecuted of our group.” In the tradition of Tubman and Truth, Thurman’s shift to an international arena, demanded “the championship … of all depressed minorities resenting [the insults delivered] to them.”22

Thurman had been leaning in this direction for at least a decade. The India travels of Juliette Derricotte, her friend, and Thurman’s own first-hand experiences of speaking to Indian women in their indigenous settings led her to promote an internationalist leadership of antiracist and anticolonial black women. She also wrote Veena, Lady of India, “a pen portrait of Indian women.” Hence, Thurman founded the Juliette Derricotte Memorial Scholarship Foundation after her return from India around 1937. Phenola Carroll, who was with Thurman in India, told a friend, “this Foundation is the work of Mrs. Sue Bailey Thurman, who has carried it almost single-handedly. It is a very mammoth but worthwhile and even necessary undertaking.” “We fight on all fronts,” Thurman declared. It was crucial that black women “establish ourselves in all parts of the world as people to be respected.” She identified “strange and sinister vehicles of propaganda” in media, books, and “mammy dolls” that damage the image of African American women. They should also develop a “philosophy of how to destroy Jim Crow.” Moreover, in addressing the condition of subject peoples worldwide, black women should be aware of “Negro women” in Cuba and Haiti. Most importantly, Thurman highlighted the importance of the Juliette Derricotte Memorial Foundation that aimed “to broaden Negro Students.”23

Just as Thurman admired Tubman and Truth for their nineteenth-century achievements, she also esteemed Juliette Derricotte for her groundbreaking travel to India a few years earlier. From non-elite origins in Athens, Georgia, where she was born in 1897, to degrees from Talladega College and Columbia University, Derricotte, as an undergraduate, became involved with the YWCA. Matriculation at the Y’s training school preceded a national position at the New York City headquarters. This connected her to the World Student Christian Federation that took her to meetings in England and India. During her seven weeks among Indians, she was awakened to the discrimination that diverse populations encountered in this colonized country. She left the YWCA for Fisk University, but after four years Derricotte died as a result of a car accident in 1931 in Dalton, Georgia. Medical treatment was denied her at a white facility, and by the time she reached a black hospital, twenty-seven miles away in Chattanooga, Tennessee, she had succumbed to her injuries. Howard Thurman eulogized Derricotte, and Sue Bailey Thurman memorialized her through the founding of the Derricotte Foundation.24

Thurman started to operate the philanthropy in 1937 for African American women undergraduates to study in India. One announcement, “Our ‘Social Ambassadors’ to India,” noted that “Mrs. Thurman being most eager to establish inter-American Negro and East Indian student relationships” went on extensive speaking tours to promote foundation objectives. Her travels included several black schools and colleges, including Lincoln University in Missouri, Bennett College, Palmer Memorial Institute, and others. She also went to Indianapolis, Roanoke, Chicago, and Detroit and visited black sororities and fraternities in Washington, DC. All of her honoraria benefited the foundation.25

Thurman told the president of Fisk University that in 1939 the scholarship targeted “a young woman of the student body of Talladega and Fisk,” the schools where Derricotte had been affiliated. Thurman at Fisk relied on the wife of a prominent professor who belonged to the Derricotte National Scholarship Committee to nominate two students. In Baltimore, Thurman had the vigorous assistance of Phenola Carroll, her Pilgrimage of Friendship colleague. Carroll, in a joint communication with a YWCA official, commended Thurman for carrying on Derricotte’s operations, saying, “Negroes have too few chances for travel in the Orient. Because of this, many wrong ideas concerning us have taken root there. This is the most effective way of giving our race a fair hearing. These girls will do a great deal toward making for better racial understanding.” Also, Carroll and her YWCA associate arranged for Indian exhibits to increase awareness of where Derricotte scholars would be going. The Druid Avenue YWCA Branch, probably due to Carroll’s intervention in the late 1930s, sponsored an Indian Tea for students and an exhibit of Indian handcrafts. As a YWCA official, she assisted Thurman in promoting Derricotte objectives.26

Thurman deployed her contacts in India and within her international YWCA network to facilitate itineraries for the students. A cooperative principal of Woman’s Christian College in Madras, India, welcomed the first of Derricotte scholars. “We would expect her to identify herself with student life.” One of the Derricotte fellows attended the Government Training College, where she interacted “with a big group of students.” Similarly, plans were made for the Derricotte awardee to spend six weeks at St. Christopher College in Madras. The YWCA official in Ceylon commended Thurman, saying that if others would emulate her then “many lovely international friendships would be established to make the world a more peaceful place.”27

Already, Thurman had described two of the Derricotte scholars as “Our ‘Social Ambassadors’ in India,” where they would study at the “most important intellectual centers [in] Lahore, Trivandrum, and Madras.” Anna Vivian Brown of Oberlin was scheduled “to attend the All-University Student Conference of India, Burma, and Ceylon in fall 1937 as a representative of Negro students in America.” Marian Martin of Howard University would go to the All-India Woman’s Conference, which, according to Thurman, “is the most significant gathering of women in the eastern world.” Both Derricotte scholars would be graduated from their home institutions in 1938. Margaret Bush of St. Louis, Missouri, a student at Talladega, became a Derricotte fellow in 1939 to study at Visva Bharati College in Bengal. Her courses included Tagore literature, the Hindi language, India’s constitution, Indian economics, and Indian dancing. She also was a part of a group studying pacifism. She met the Tagore and was involved in an interview with Gandhi. She spoke on “Some Aspects of the Negro in America” and explored the possibility of launching a center for “Negro culture” at her Indian college.28

Thurman also wanted an Indian woman to come as an exchange scholar to “live a year of her college life in a cultured Negro home” and to benefit from “one or more of our best Negro colleges.” In this way, “an Indian girl, and we, as Americans of color, would be able to exchange with each other,” depending on the availability of an African American student who could go to India. The Indian student, however, was deemed too young, and the black student could not consider a “six month trip to India unless her mother could go with her.” Nonetheless, Thurman, despite some negative reports from the Derricotte fellows and from some who observed them, believed “that my choice of girls to initiate Negro student study in India was a good choice.”29

As significant as Sue Bailey Thurman in her personal and programmatic interactions with Indian women, which through the Derricotte program lasted less than three or four years, was Blanche Wright Nelson, “a well known social worker” (fig. 2). Born in Memphis and connected to the elite Robert R. Church family, Nelson was educated at Teachers College at Columbia University, became an elementary school principal in Memphis, and had extensive experience in women’s work in the War Camp Community Service. She moved to New Haven, Connecticut, as the first administrator of the Dixwell Community House and met William Stuart Nelson, a Yale Divinity School student. Her fiancé had seen action in France as a World War I army officer and had been a student at the Sorbonne and at the University of Berlin. He returned to Germany with his new bride in 1926 to matriculate at the University of Marburg.30

Blanche Wright Nelson (William Stuart Nelson Papers, Moorland-Spingarn Research Center, Howard University, Washington, DC).

Her residence with her husband in Europe preceded his stellar academic career from the late 1920s through the 1930s as a professor and administrator at Howard and as president of Shaw and Dillard. When he became dean of Howard’s School of Religion in 1940, Nelson increasingly focused on studying Gandhian nonviolence as a moral methodology to effect African American advancement. He deepened his query through a sabbatical in India sponsored by the American Friends Service Committee (AFSC). During their stay in India in late 1946 and in most of 1947, Nelson headed the Calcutta Service Unit, an AFSC facility for relief and educational programs, and lectured throughout India on “interracial and international understanding.” Additionally, he wanted to learn more about the intersection of Gandhian nonviolence and Quaker pacifism. His consultations with Gandhi were extensive. Perhaps, more importantly, he traveled with the Indian leader at several sites of interreligious violence between Muslims and Hindus due to the 1947 India-Pakistan partition. Nelson was an eyewitness to the moral authority of the Indian leader as he calmed some of the outbreaks. The AFSC tapped the Nelsons as a couple, with a special assignment given to Blanche Wright Nelson to “help organize welfare centers and train Indian community workers.” Her involvement with religiously and ethnically diverse groups of Indian women occurred during this period of decolonization. She observed firsthand the issues that colonialism and culture imposed on India’s female population.31

Blanche Nelson acknowledged that her role at the Calcutta Service Center principally lay in relief programs and in training professionals about improving services to their clients. She noted that “I worked specifically with small Moslem girls and a most unusual group of college men and women [and] young teachers [who] made up a cross-section of Indian cultures and some Europeans and Americans.” Nonetheless, Nelson envisaged her work far more expansively than what AFSC officials may have intended. She contacted the Bombay-based Tata Institute of Social Sciences about participation in the All-India Conference of Social Work probably set to occur during Nelson’s stay in India in 1947. Beyond her particular duties at the service center, Nelson obviously wanted to pursue her assignment within a broad understanding of the systemic needs of vulnerable populations in a hugely diverse, decolonizing nation of 390 million people.32

Even without an affiliation with the All-India social work group, Nelson was involved in sundry health, education, and intergroup initiatives aimed at the amelioration of interethnic and interreligious tensions. Her visit to the site of a midwifery project, while significant, did not claim the lion’s share of her time. A “little project with Muslim girls and young women,” she observed, “grows increasingly in our interest and affection.” These thirty girls, all from a bustee, or slum, ranged in age from six to twelve and came five times a week to an AFSC facility. Here, Blanche Nelson personally provided them with important instructional services. She recognized, for example, their minority status as Muslims in a majority Hindu society and addressed their “need for religious instruction in their ancestral faith. Hence, she arranged for them to learn Arabic so they could better understand the Quran. Urdu, a language derived from Hindustani that Indian Muslims mainly spoke, was “the mother tongue of most of the girls.” Nelson, however, endorsed their desire to learn English. “To speak English,” she realized, “is the hallmark of education” and a ladder to better opportunities. Nelson, though cheered by their ambition, worried that these young girls were trying to learn too many languages at one time. Her intimacy, from the perspective of these Muslims, was notable, because within the small population of Westerners in Calcutta “only a very, very few have the desire to know and to be associated with Indians.” Nelson hardly despaired, because six “young Muslim women” volunteered to assist in the project. One of them, Nelson was delighted to note, belonged to the Bengal Muslim Women’s Association. It was her hope these minority religious women would continue services to her “little venture” after she returned to the United States.33

The transition from British rule to partition between India and Pakistan and to Indian independence exposed the region to increased conflict between Hindus and Muslims. In this context of interreligious violence over the split into two countries, Blanche Nelson organized an international group of more than thirty young people. Because of too few “Westerners,” Nelson contacted several consulates to help in recruitment. One ally was the consul general of France who promised to locate “French speaking Indians.” “I am especially proud,” Nelson said, “of the young Muslim men and girls who are a part of the group.” Though Nelson did not achieve numerical balance because of too few Europeans, the impressive aggregation of Indian groups included Hindus, Muslims, Christians, Gugeratis, Tamilians, Sindhis, Rajputans, Tellegues, Sinhalese, Assamese, Malavolams, and Bengalis.34

Later, she was cheered by the addition of a Sikh and a Burmese. Though presentations of Indian culture, especially music and dance, were highlighted, Nelson had a larger purpose in mind. “At a time when tensions are so great in Calcutta,” she declared, “we have thought it wise to center our attention on building the friendships and on those interests where there is agreement rather than plunge immediately into discussions of a controversial nature.” She believed initiatives to promote dialogue between Westerners and Asians in countries like India were useful. Unfortunately, Nelson’s group, she surmised, “is the only group of its kind presently active in Calcutta. A similar group once fostered by the YWCA has fallen apart and the East-West Fraternity is no longer active.”35

The partition, a residue of British colonial map making, remained problematic. The independence of India, noted Nelson’s Muslim volunteers, “had no meaning for them,” and “they would not rejoice.” Their angst, Nelson reported, drew from “some uncertainty” among her Muslim associates about who would be permitted to stay in Calcutta and who would be compelled to settle in Pakistan now that their native Bengal would be partitioned. The feelings were intense, Nelson said, because her volunteers were politicized and “[were] very ardent Muslim Leaguers.” Nonetheless, they agreed that despite the fact that Muslims were being pushed out of their homes and compelled to live in Pakistan, “the little ones” whom Nelson was teaching would be urged “to love foreigners and Hindus as well as we love ourselves.”36

Independence from the British arrived in August 1947 and with it the creation of two nations, one majority Hindu and the other mainly Muslim. Nelson observed that one “could never understand the magic transformation which came to this great city [of Calcutta] torn for as many long months by fratricidal strife.” Fortunately, “Hindus greeted Muslims, and Muslims greeted Hindus.” She concluded, “there is much quiet solid work that [must] follow this first burst of enthusiasm.” She hoped that “old scars and wounds may [not] open to bleed again.” With independence, “a fine new beginning has been made and I have great faith in the future which lies ahead for the new nation.”37

Blanche Nelson recalled that her husband, during India’s interreligious violence, accompanied Gandhi “from village to village in his efforts at reconciliation [and] to learn from him the deepest meaning of nonviolence and its practical application.” She focused, however, on forging “friendships” within India’s diverse and, at times, contentious populations. Both Nelsons, who spoke in various venues about the African American experience, deployed this perspective to test in India moral methodologies that could be useful in the African American freedom struggle. At the same time, Blanche Nelson, through her on-the-ground activities, understood the consequences of colonialism and the rivalries that it aggravated across India’s complicated religious landscape. Reconciliation, both Nelsons believed, was key to nation building in a newly independent India. An AFSC official crudely concurred with the Nelsons. In soliciting feedback about their effectiveness, she said “the fact that they were of a darker race may have been a helpful element in the particular situation of tension with which the Calcutta Centre deals.” It appeared “that they have made a real contribution” and that “another Negro couple” should succeed them. However inelegantly expressed, it seemed that Blanche Nelson, as an African American woman, enhanced her credibility with Muslim women and showed her impressive understanding of their dual predicament in poverty and in a minority religious status.38

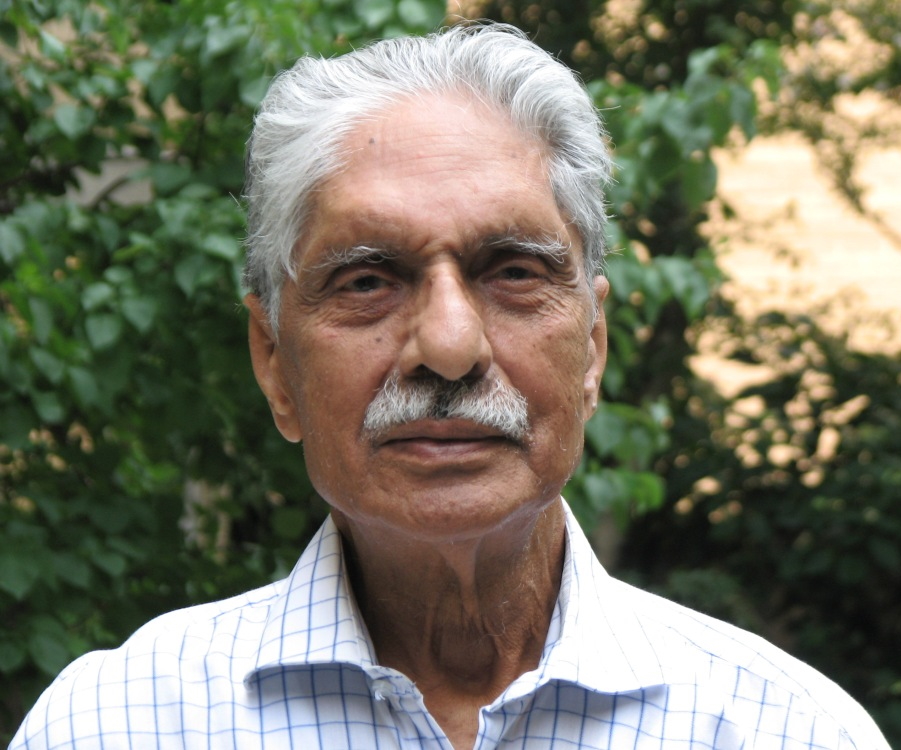

Blanche Nelson’s bustee project in Calcutta among poor Muslim girls suggested that economic uplift was another integral component of India nation building. This view also resonated in the early 1950s with the International Conference of Social Work. The poverty of those in lower castes and others penalized as religious minorities may have motivated the organization to tap Sadie T. M. Alexander (fig. 3) to attend their global gathering in India in 1952. Alexander, born in 1898 and a contemporary of Thurman and Nelson, had greater visibility than her black women counterparts. Alexander, an attorney, a PhD in economics, and the granddaughter of an AME bishop, had been head of Delta Sigma Theta sorority and the official lawyer for her denomination’s council of bishops. Most importantly, she belonged to President Harry Truman’s Commission on Civil Rights whose hard-hitting report, To Secure These Rights, identified pressing issues that influenced the burgeoning Civil Rights Movement.39

Sadie T. M. Alexander (Sadie T. M. Alexander Papers, University Archives and Records Center, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia).

Apparent to Thurman and Nelson was the juxtaposition between racial issues in the United States and colonialism and decolonization in India. The invitation to Alexander to visit India was framed in this same context. As a member of the American delegation to the social work conference, she also interacted with the United States State Department, which facilitated the trip along with “Background Papers” from the Office of UN Economics and Social Affairs. Chester Bowles of the Foreign Service, for example, suggested that Alexander pay attention to developments in India’s infrastructure of newly built dams and their relationship to enhanced agricultural production aimed at the reduction of the “food deficit.” At the same time, the State Department, through the US Information Service, provided Alexander with “What Are the Facts about Negroes in the United States?” The pamphlet referred to Truman’s civil rights commission, of which Alexander was a part, saying that “discrimination needed to be combated and recommended detailed action for the federal and state governments, private organizations and individuals to take.” The objective of the publication lay in propaganda about the progress of African Americans and the diminished barriers to their advancement. Alexander, a signatory to To Secure These Rights, the Truman civil rights report of 1947, knew better. She also received an informational pamphlet, “What Are the Facts about American Aid to India?” The new nation, a populous democracy, was commended for seeking “to raise the living standards of her people to banish disease, illiteracy, poverty, and despair, without resorting to violence.”40

At the social work conference, Alexander participated in seminars surrounding the theme “The Role of Social Services in Raising the Standard of Living.” Sessions were held on services for children and youth, the handicapped, a range of welfare issues, and population problems. These subjects echoed some of the same poverty concerns that Blanche Nelson identified as crucial for an independent India. In her India trip, Alexander, in a sense, assumed Nelson’s mantle.41

Alexander’s three-week stay in India was shorter than Thurman’s and Nelson’s time spent in the region. She also valued the same indigenous interactions that brought African American women together with Indian peoples. The visit to Poona, she said, “turned out to be one of the most profitable parts of the trip,” especially the encounter with Indian women who served Indian cuisine to the American delegation. The positive response to this occasion reflected the normative perspective that African American women brought to their solidarity with Indians. This effort improved living standards, particularly for women and children, and mirrored the agenda African American women pursued in the United States.42

As program administrators, participants, and observers of targeted activities with Indian women, African American women travelers educated their counterparts about their struggles in the United States and helped them to navigate dislocations related to decolonization and partition. Involvement with nongovernmental organization and State Department initiatives in India between 1935 and 1952 allowed black women to critique colonialism, ameliorate its effects, and provide opportunities for African American women to empower those whose economic and religious vulnerabilities had been spurred by colonialism. The altruism of African American women also redounded to their benefit through an exposure to nonviolent methodology and its possibilities to achieve African American liberation in the United States. Sue Bailey Thurman, after her return from India, said in a talk to an audience of about 650 at Oberlin College that African Americans should emulate Indians, who united in their fight against British colonialism. Indian women, through these interactions, also learned that parallels, though uneven, between themselves and African American women reflected similar structures of hegemony that warranted the mobilization of women’s global alliances.43

.....................................................................................................................................................

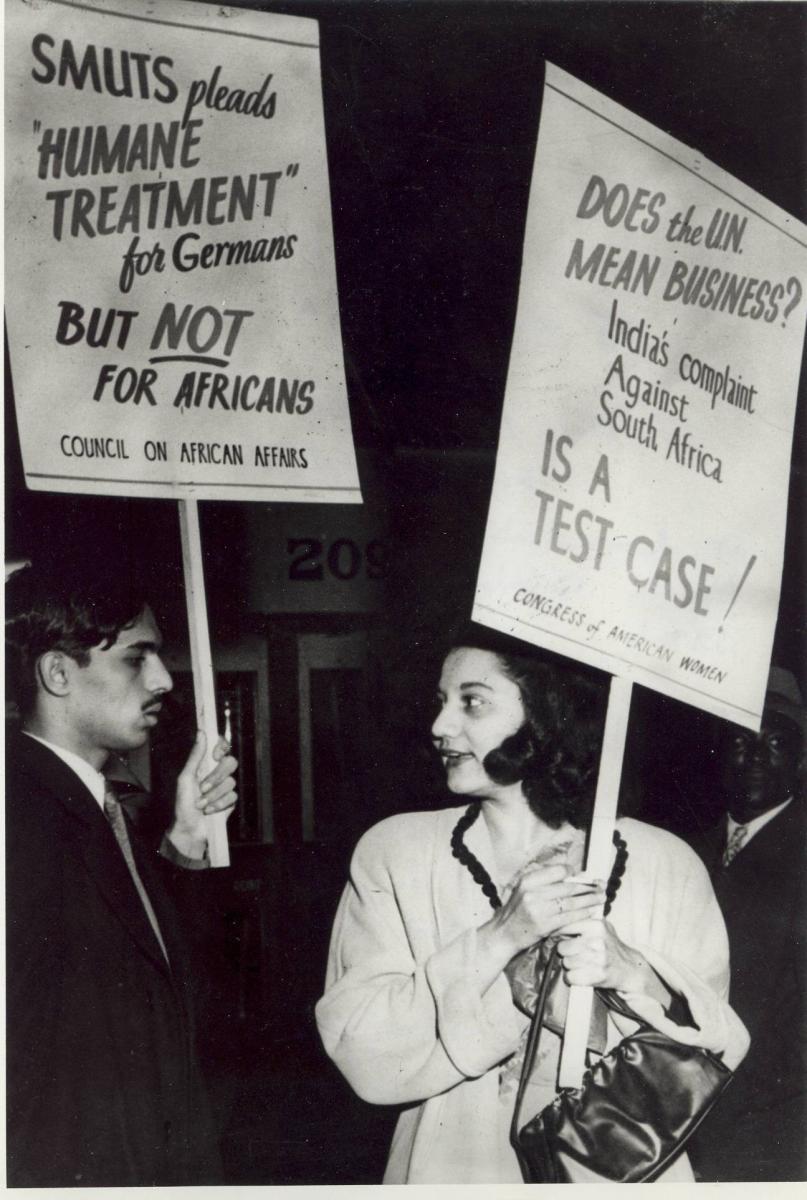

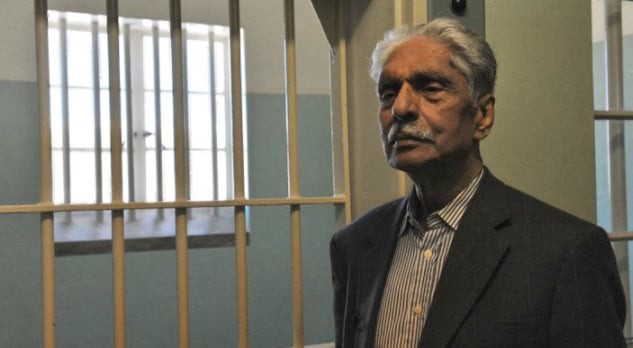

E. S. Reddy with Oliver Tambo, President of the African National Congress, at a special meeting of UN Anti-Apartheid Committee in 1981 | Yutaka Nagata/UN Photo

India's Gift to the Struggle against Apartheid

In late 1946, two iconic leaders of the African-American community, Paul Robeson and W. E. B. Du Bois, organised a protest in front of the South African consulate in New York. The white supremacist South African government had enacted legislation – the “Ghetto Act” – to restrict the property rights of Indians. This led to the first mass protest by Indians in South Africa since the departure of Gandhi from its shores. The New York picket line was assembled to protest against the repression of the Indian passive resistance campaign and a strike by mine workers. Amongst the protestors were a group of young Indians brought there by a student at New York University, E. S. Reddy.

While he was literally fresh off the boat, having arrived in America earlier that year, it is unsurprising that Reddy would join the protest. He had come of age in a period when India's long struggle for freedom was about to bear fruit. Moreover, there was a sense of affinity with South Africa's Indians owing to the Gandhi connection. But what was altogether exceptional was that from that first protest onwards, Reddy would dedicate his life to fight for the end of racial discrimination in South Africa. As the African National Congress recalled in its statement on his passing on 1 November 2020 in Cambridge, USA, Reddy had stayed steadfast to his belief: “I cannot feel free, as an Indian, until South Africa is free of apartheid.”

Enuga Sreenivasulu Reddy was born on 1 July 1924 in the village of Pallaprolu, near Nellore in present-day Andhra Pradesh. With the family in debt, his father had to seek a formal job and they moved to Gudur. Growing up with four brothers and a sister, Reddy graduated with a BA from Madras Christian College in 1943. Like many others, he was eager to travel to the west for his education but did not wish to go to the country that had colonized India, the United Kingdom. Once the Second World War ended, he took the first available ship and arrived in America in March 1946.

He had intended to go to the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign to study chemical engineering, but owing to the dislocation of the times arrived rather late for the term. Thereupon he changed his plans and enrolled for a Masters in International Relations at New York University. Upon graduating in 1948, Reddy moved to Columbia University to pursue a PhD in Public Administration. But by this time he was utterly broke and could not continue his studies any further. In 1949 he obtained a position at the recently established United Nations Organization. A year later he was married to the Turkish scholar Nilufer Mizanoglu with whom he was to have two daughters (some details are available here).

All through the era of the South African struggle, India had played a critical role. This was owed to the legacy of both Gandhi and Jawaharlal Nehru.

1946 was a significant year. A catastrophic global war had just ended and many countries were counting their losses and picking up the pieces. As Victor Sebestyen shows in his global history 1946: The Making of the Modern World, the decisions taken in that year have profoundly shaped our contemporary world. Sebestyen's narrative is sweeping but there is a yawning gap as regards the events in the African continent. Many Asian countries – notably India and China – were to soon become free or be decisively transformed. But Africa continued to be in the grip of the twin curses of the 20th century – colonialism and racism. However, change was afoot and the mass protests of 1946-48 in South Africa were to inaugurate a long period of struggle that ended with the release of Nelson Mandela in 1991 and the formation of that nation's first democratically elected government in 1994. Reddy played a fundamental role in the global campaign of solidarity that helped put an end to apartheid.

All through the era of the South African struggle, India had played a critical role. This was owed to the legacy of both Gandhi and Jawaharlal Nehru. In 1946 the Ghetto Act and the subsequent crackdown against protestors in South Africa had aroused strong passions in this country. Amidst the turmoil of the period, the strength of popular sentiment forced the Viceroy, Archibald Wavell, to place a trade embargo against South Africa. Subsequently the interim government of Nehru took a more active position, with action moving to the United Nations. With both Gandhi and Nehru deeply concerned about the ominous segregationist developments in South Africa, India played a key role in the United Nations (UN) to make South Africa's actions a matter of global scrutiny (See Bhagavan 2013).

The UN was never truly representative and by 1950 America's Cold War mentality and McCarthyism had permeated the organisation. Reddy found “the atmosphere to be oppressive”, but his job allowed him to read up on South Africa on “company time”. He recognised that his NYU education in international relations was tainted by racist beliefs and a hatred of nationalism in the colonies. Reddy felt he was saved from taking offence by his sense of humour, but knew that he had to jettison such baggage and “think with my blood”, i.e. in terms of Indian nationalism that included solidarity with other oppressed peoples.

Even before E. S. Reddy left India, he had read some pamphlets on the problems in South Africa which triggered his interest and a sense of commitment.

Like many of his generation, Reddy respected Gandhi but it was Nehru's socialist and internationalist outlook that he found more appealing. Even before he left India, he had read some pamphlets on the problems in South Africa which triggered his interest and a sense of commitment. Now he felt a personal responsibility towards aiding African countries in their struggle against colonialism and racism.

In the meanwhile, the brutal oppression of the South African regime was resisted by the Defiance Campaign of 1952. This was the first large-scale protest carried out jointly by the South African Indian Congress and the African National Congress wherein activists defied the apartheid laws that placed many restrictions, including the ability to move freely without permits. As Reddy was to later write, the Defiance campaign “shattered the stupid racist myth that the African and black people were somehow incapable of an organised and disciplined nonviolent resistance.” At the UN, he ran afoul of his boss for agreeing with the Indian government's argument that the apartheid laws were not a domestic matter as South Africa insisted, but a gross violation of the UN Charter. He was shunted out to a different desk but when a commission on racism in South Africa was established, Reddy was brought in owing to his already well-developed understanding of that country and its problems.

Reddy toiled away at his job preparing reports and organising meetings, with little impact. With the main western powers backing South Africa, Reddy reckoned that the challenge to apartheid could not gain traction until Africa was decolonised and its free nations could participate in the UN on their own terms. A 1962 resolution called for the ending of diplomatic ties with South Africa and, thanks to Reddy's effective lobbying, the appointment of a full time body which came to be known as the UN Special Committee Against Apartheid (see Konieczna 2019). He became the Principal Secretary of this committee and served in this and related positions till his retirement in 1984 with the rank of Assistant Secretary-General.

It is generally believed that the widespread international pressure helped prevent the death sentence being imposed [in 1963] on Mandela and his comrades.

Soon after its formation, the Committee Against Apartheid faced its first major crisis. In 1963, the South African regime began the trial of Nelson Mandela and his colleagues for acts of sabotage and attempting to overthrow the government. The Rivonia trial became a global cause celebre as it was feared that the defendants would be awarded the death sentence. In an unprecedented move, the UN General Assembly almost unanimously adopted a resolution calling for the end of the trial and the release of all those imprisoned for their opposition to apartheid. The resolution was supported by 106 countries against one opposing vote – that of South Africa. That resolution was drafted by Reddy who worked alongside African diplomats and successfully convinced a handful of reluctant western nations to support the motion.

It is generally believed that the widespread international pressure helped prevent the death sentence being imposed on Mandela and his comrades. Rivonia came to be known as “the trial that changed South Africa” and Nelson Mandela became an international hero for his fearless statement in court that a democratic and free South Africa was “an ideal for which I am prepared to die”.

At the UN the major western powers boycotted the Committee Against Apartheid and it was expected that their intransigence would make the committee a worthless endeavour. But Reddy was not to be deterred and he hunkered down for the long haul in a tricky and hostile work environment. Years later he noted that in the event, “the Committee proved to be very influential and effective.” What he left out was the fact that this effectiveness of the committee was owed overwhelmingly to his own exertions. Reddy was soft-spoken and polite, but he could not be accused of false modesty. He recalled that he did not know of any other UN official who worked on “an issue with equal determination and conviction”. Over two decades he worked seven days a week, put in 70-80 hours of work and took no holidays or vacations.

On occasion Reddy had doubts about the value of his labours. But he was reassured by his vast network of friends in the various African liberation struggles who recognised the significance of his work at the UN.

Since South Africa continued to command the support of permanent members of the Security Council such as the USA and the United Kingdom, Reddy worked on moving the action to other fora, both within and outside the UN. He was innovative in getting NGOs and individuals involved in the struggle, including ANC leaders, to depose in front of the Committee which kept the focus on the cause. Throughout his tenure, Reddy also produced an endless stream of reports for use by campaigners. When he visited the offices of the British Anti-Apartheid Movement, Reddy noted that a table had only three legs. The role of the missing leg was served by a stack of old UN reports he had written!

For a long period, these efforts had little impact. On occasion Reddy had doubts about the value of his labours. But he was reassured by his vast network of friends in the various African liberation struggles who recognised the significance of his work at the UN. While he worked primarily on South Africa, it must be remembered that the liberation of all of Africa was what he desired. Later in life he commented that “With the redemption of Africa, a shameful era of human history — of imperialism and colonial domination will soon come to an end, and humanity would have confronted what the Pan African Movement defined in 1900 as the problem of the twentieth century, the problem of the 'colour line'.”

With not much progress on the question of apartheid at the UN, Reddy recognised the need to build pressure from the outside. Decades later when a scholar interviewed anti-apartheid activists, they all independently pointed out Reddy's influential role in this regard. He was that rarity, an “activist public official” (see Thorn 2006). He conducted a number of conferences across the world to raise awareness and build a network of solidarity across borders on the question of apartheid. He also worked with smaller European nations that did not share in the political positions and colonial attitudes of the major powers. As a result he developed a close relationship with the Swedish Prime Minister, Olof Palme, who emerged as an influential western opponent of apartheid. Some believe that Palme's assassination in 1986 was at the behest of the South African regime.

He also became a friend and supporter of the President of the ANC, the legendary Oliver Tambo, who had gone into exile to build global support against apartheid. In 1965, Reddy shrewdly advised Tambo that the latter should not talk of the South African question as a colonial problem but pose it as a racial one. Reddy argued that since South Africa was not a colony, talking about apartheid in terms of colonialism would harden the attitude of European powers such as Netherlands who would interpret it as implying that the ANC intended to expel the white population out of South Africa. Incidentally, Tambo was able to travel freely while in exile and carry out his extraordinary work in mobilising world opinion thanks to an Indian passport given to him by Nehru's government.

Following Reddy's suggestion to the then foreign minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee, in 1979 the Indian government bestowed upon Mandela the Jawaharlal Nehru Award for International Understanding.

The South African government was spending some $15 million annually for propaganda that demonised the ANC and its leadership. It was necessary to counter this well-oiled publicity machinery by building a groundswell of popular support. While many Western governments were duplicitous on apartheid, in an age of mass democracy they were not immune to public opinion in their own countries. The global sports boycott of South Africa was one such successful endeavour, in which Reddy played a part.

Meanwhile, after a conversation with the ANC activist in exile Mac Maharaj, he proposed to a network of activist and civic groups that Nelson Mandela's 60th birthday (18 July 1978) be celebrated as a public event. The campaign resulted in more than ten thousand letters of greetings and solidarity being sent to Mandela and his wife Winnie, both in different prisons, and major public events such as the Free Mandela concerts in Britain. 'Mandela Fever' helped transform the widespread scepticism about the man to one of admiration and even adulation. Following Reddy's suggestion to the then foreign minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee, in 1979 the Indian government bestowed upon Mandela the Jawaharlal Nehru Award for International Understanding. This was the first such significant honour for Mandela and opened the doors for similar awards that highlighted his imprisonment and helped change public perception.

During his career at the UN, Reddy brought an appetite for hard work, a prodigious memory and an unerring command of facts to bear on the problem of apartheid.

Diplomacy and lobbying are the unglamourous aspects of aiding a revolutionary struggle. The enormous burden and costs of the struggle against apartheid were borne by South Africans themselves. But the decades of global solidarity were crucial in making that evil regime untenable. In this transformation, Reddy played a pivotal, indeed indispensable role. In 2013 the South African government honoured him with an award named after his friend of long years, the Order of the Companions of Oliver Tambo. Reddy could look back in satisfaction that since reading his first pamphlet on South Africa in 1943, he had been an unfailing champion of freedom in South Africa and the African continent itself.

During his career at the UN, Reddy brought an appetite for hard work, a prodigious memory and an unerring command of facts to bear on the problem of apartheid. Upon retirement in 1984, his irrepressible energies and commitment found other channels of expression. While this included documenting the South African struggle that he knew so well and was part of, Reddy also returned to the man who had been a quiet presence in his life all along—Mahatma Gandhi. As part of our freedom struggle, Reddy's father had spent three months in prison in 1941 and his mother had donated her jewels to Gandhi's campaign against untouchability. The eight-year-old Reddy first saw the Mahatma on the 20th of December 1933 at a public meeting in Gudur and went around the meeting with an upturned Gandhi cap to collect a few pies for the cause.

While he lived and worked for more than seven decades in the US, Reddy remained a proud holder of an Indian passport.

With his extraordinary capacity for industry and a nose for ferreting out rare documents, for many decades Reddy was a vital figure in the study of Gandhi's life. He single-handedly produced a very large body of essays and collections that reflected on different aspects of the Mahatma's life and also highlighted novel sources of understanding. For many students of Gandhi's life, this writer included, he was a vital guide that one could always rely upon. He was unusual in his scrupulous attention to detail, an ability to work with a large number of collaborators and the generosity with which he gave away the fruits of his research findings for others to use.

In his New Year's greetings for 2016, into his tenth decade, Reddy told his friends: “I look forward to a busy year ahead, as I am still able to do research, edit and write.”

While he lived and worked for more than seven decades in the US, Reddy remained a proud holder of an Indian passport. His life was shaped by the values of an India that had non-violently fought for its freedom, but also saw its fate as inextricably bound up with that of other oppressed peoples around the world. During the freedom struggle, India had the services of a number of Britons who gave themselves to a cause they believed to be correct, the end of Empire. C. F. Andrews, Reginald Reynolds, Agatha Harrison, Muriel Lester, Madeleine Slade (Mira Behn) and Fenner Brockway are a few such names. In going beyond the confines of one's own nationalism to embrace the righteous causes of the world as one's own, E. S. Reddy is a rare Indian name in this vein.

The world that Reddy has departed from is very different from the one he had entered in 1924. European colonialism is a thing of the rather distant past, but peoples and nations across the planet grapple with the problems of inequality and injustice amplified in our contemporary times. India seems to be on the edge of a precipice where it is about to fully shed the legacy of its freedom struggle. In South Africa, the ANC is a pale shadow of its revolutionary past and mired in all manner of crises of legitimacy. Yet one must never forget that the struggles in these two countries were central to the transformation of the world in the 20th century.

At a time when most societies are turning intolerant, insular and ignorant about the lives of others, the life of Enuga Sreenivasulu Reddy offers a lesson in its passion and commitment to democracy, to justice and solidarity across borders and creeds.

The author thanks Ramachandra Guha for his comments on this article.

=============================================

‘I shall not retreat’: Recalling Paul Robeson’s support for India’s freedom struggle

April 9 marks the US activist-singer’s 125th birth anniversary.

In April 1958, Paul Robeson’s 60th birthday was celebrated in several cities in India. These celebrations were organised by an all-India committee under the chairmanship of MC Chagla, the former chief justice of the Bombay High Court. This committee had been initiated by Indira Gandhi, who had consulted with Jawaharlal Nehru about the possibility of celebrating Robeson in India. The prime minister had readily agreed.

By this time, Paul Robeson was a famous singer and actor known around the world. The American government had confiscated Robeson’s passport in 1950, claiming that “Paul Robeson’s travel abroad at this time would be contrary to the best interests of the United States”. It was only after the celebrations of 1958, where people around the world rose up in solidarity for Robeson that the battle for his passport was finally won and he was able to travel again.

The American government immediately reacted to the possibility of these celebrations being held in India. The Consul-General of the US visited Chagla trying to pressure him to stop the event. Nehru had written earlier to Chagla, “I gather there is a good deal of excitement and some distress in the upper circles in the United States about this celebration of Paul Robeson’s sixtieth birthday in India.”

In the opinion of the American ruling elite and its Cold War world view, a celebration of Robeson would confirm that India was drifting into the “communist camp”. It was incomprehensible to them that India might admire Robeson on its own terms, that there were revolutionaries in India who were not necessarily communist but not anti-communist either. They were staunchly anti-imperialist and instinctively associated with Robeson’s struggle.

Indeed, in his address at the celebration, Chagla said, “Robeson was fighting against the insolence and arrogance of a ‘superior’ race, and the sense of dominance which comes from a lack of pigmentation in the skin.” He added, “If there is a God, and God is only another name for compassion and kindness, the Negroes must be dearer to Him than any other people.”

Chagla was referring to the consciousness that shaped the time: the idea that the darker nations and peoples of the world who had faced or were still facing colonialism and neo-colonialism had common cause. The fight against racial discrimination was linked to the fight against colonialism and western supremacy. This is why celebrations for Paul Robeson were held around the worldm including in Africa and China.

There are some parallels to the situation today as we observe Paul Robeson’s 125th birth anniversary. In the neo Cold War view of the US ruling elite, it is incomprehensible that India does not toe the western line on foreign policy. Meanwhile, many nations of what is termed the global South are recognising the era of western domination is over. is worth remembering Paul Robeson’s close relationship with the darker nations of the world and the reason they celebrated him.

Communicating through song

Robeson

is usually remembered as a singer but he was in fact a great thinker

and philosopher. Songs, for him, were a medium to communicate his ideas

and a way to understand the commonality of working people around the

world. “I have found that where forces have been the same, whether

people weave, build, pick cotton or dig in the mines, they understand

each other in the common language of work, suffering and protest,” he

once said. Robeson was devoted to singing folk songs, by which he meant

“songs of people, of farmers, workers, miners, road diggers…that come

from direct contact with their work”.

One of the members of the 1958 Indian committee to celebrate him, Kamaladevi Chattopadhyaya, had written, “When Paul Robeson sings he becomes something more than a singer. He transcends all human limitations and becomes the disembodied melody, which knows neither colour nor race. He interprets the ageless, deathless spirit of his lost land of Africa, his priceless heritage, before which even the hooded order of bigotry and hate spontaneously retreat.”

In 1937, Robeson founded the Council on African Affairs, with the objective of fighting for African freedom and educating the American people about Africa. The Council led several struggles particularly against the apartheid regime in South Africa. In 1944, the Council held a conference in which Kwame Nkrumah, who was to become president of Ghana, participated. The Conference came up with a six-point programme to provide concrete help to the African masses and strengthen the alliance of progressive Americans with Africans.

In June, 1946, the Council on African Affairs organised a “For African Freedom” rally at Madison Square garden. At the rally, Robeson said “The race is on–in Africa as in every other part of the world– the race between the forces of progress and democracy on the one side and the forces of imperialism and reaction on the other.”

Earlier, in September 1942, when the Congress leadership was in jail following the Quit India movement, the Council on African Affairs had organised a Free India rally. Speaking at the rally, Robeson told the audience how he had toured Spain with Krishna Menon and become friends with Nehru, Vijay Laxmi Pandit and others while he was in London in the 1930s. Another speaker at the rally was Kumar Ghoshal, a little-known Indian revolutionary who was a member of the Council on African Affairs. Kumar Ghoshal would bring ES Reddy into the Council on African Affairs. Reddy was later to play a huge role in the struggle against Apartheid in South Africa.

The membership of the Council on African Affairs was largely composed of African-Americans. Paul Robeson’s support for India’s freedom reflected the support of the African American people. In October 1942, right after the council rally, the Pittsburgh Courier, a leading black newspaper in which Kumar Goshal had a column, took a survey of black Americans on whether “India should contend for her rights and liberty now.” Close to 90% responded with “yes”.