The opium trader who became one of India's richest men

The philanthropist and businessman’s relationship with colonialism is a complex legacy

On his fourth trip to China, Jamsetjee Jejeebhoy was captured by the

French. It was the middle of the Napoleonic Wars and hostilities between

the British and the French had carried over to the Indian Ocean.

Jejeebhoy was on a British ship called the Brunswick when, off the coast of Point de Galle in present-day Sri Lanka, it came face to face with two French frigates. The Brunswick

was a trade ship and didn’t have much of a crew. They didn’t stand a

chance. The passengers, mostly merchants like Jejeebhoy, were taken

hostage to South Africa. They were released there but had no way to get

home. It took Jejeebhoy four months to make it back. But when he did,

his life had changed forever. He had made friends with the Brunswick’s young doctor, William Jardine. This chance meeting turned, as historian Jesse S. Palsetia writes in his book Jamsetjee Jejeebhoy of Bombay, into a friendship “that would change both men’s lives and influence the course of history.”

When Jejeebhoy met him, Jardine’s time as a doctor of the East India Company was almost at an end. He had plans to set up a trading house in Canton, now known as Guangzhou. That trading house still exists, as a conglomerate with a market capitalisation of more than $40 billion. Jardine’s firm would become so enormously successful because it was soon going to corner the market on one particular commodity, one that was much more profitable than cotton, and one whose demand was exploding because the British had got millions of Chinese hopelessly addicted to it: opium.

Opium wasn’t just another trade good for the British Empire. It was the necessary corollary to another commodity: tea. The British were importing tens of millions of pounds of tea from China every year. There seemed to be no end to the demand and everyone involved was making huge profits. There was just one problem. They didn’t have the cold hard cash or rather, cold hard silver to pay for it.

With all of the Empire’s physical currency disappearing into China,

the British were running a huge trade deficit. They needed something

that the Chinese wanted as much as they wanted tea. Opium was the

answer. And it was essential to keeping the Empire’s entire economy

afloat.

With all of the Empire’s physical currency disappearing into China,

the British were running a huge trade deficit. They needed something

that the Chinese wanted as much as they wanted tea. Opium was the

answer. And it was essential to keeping the Empire’s entire economy

afloat.

Shipped from Bombay

The opium came from the East India Company’s nearby colony, India. It was grown in Malwa and shipped from Bombay. At its height, almost one-third of the entire trade was going to one firm, Jardine’s trading house in Canton. And the man who enabled this trade from India was becoming stunningly wealthy.

By the time he was 40, Jamsetjee Jejeebhoy had allegedly made more than ₹2 crore — in the 1820s. He was already one of the richest men in the entire country, but he had his eye on even greater prizes.

The life of Jamsetjee Jejeebhoy makes for an excellent story. It neatly divides into two acts. In the first act, Jejeebhoy lives a life of adventure and daring. In the second act, he becomes an elder statesman, a civic figure working for the benefit of the community. This is no accident. Jejeebhoy’s ambitions were sophisticated and manifold. They would’ve been far out of reach for anybody who wasn’t willing to reinvent themselves. Even in his earliest days, there are signs that Jejeebhoy was conscious of his persona, taking steps to change details of his life to better fit his desired narrative.

For example, he repeatedly claimed to have been born in Bombay but a

number of historians believe that he was actually born in Navsari in

Gujarat. He also changed his name from Jamshed to Jamsetjee, allegedly

so that he would seem more like a member of the mercantile Gujarati

community. Undoubtedly, the capital and networks of the broader Parsi

community were essential to his success, but in this way at least he was

a self-made man.

For example, he repeatedly claimed to have been born in Bombay but a

number of historians believe that he was actually born in Navsari in

Gujarat. He also changed his name from Jamshed to Jamsetjee, allegedly

so that he would seem more like a member of the mercantile Gujarati

community. Undoubtedly, the capital and networks of the broader Parsi

community were essential to his success, but in this way at least he was

a self-made man.

His early life was marked by tragedy: he lost both his parents before the age of 16. His family was from a Parsi priestly community but his father worked as a weaver. After they died, Jejeebhoy moved to Bombay and began working for his maternal uncle, buying and selling empty liquor bottles. He earned the nickname ‘Batliwalla’ or bottle-seller and seemed to revel in it, often signing letters with the moniker as if it actually was his last name.

At 20, he married his maternal uncle’s daughter, Avabai, who was around 10 years old at the time. And through his family, he began to trade, making five trips to China. None of these trips directly made him rich, but they did make him vital connections across South and East Asia, including, of course, William Jardine.

Vital connections

Jamsetjee began his trading firm, Jamsetjee Jejeebhoy & Co, with

three other partners, each from a different community. There was

Motichund Amichund, who was Jain and had close ties to the opium

producers in Malwa. There was Mohammed Ali Rogay, a Konkani Muslim, who

was a ‘Nakhuda’ or ship-owner/ captain. They were joined by the Goan

Catholic Rogério de Faria, who had connections with the Portuguese

authorities that controlled the port at Daman. Initially, the existence

of Daman was a thorn in the side of the British who tried to restrict

the export of opium through Bombay alone. They eventually gave up and

settled for taxing the produce at its source.

Jamsetjee began his trading firm, Jamsetjee Jejeebhoy & Co, with

three other partners, each from a different community. There was

Motichund Amichund, who was Jain and had close ties to the opium

producers in Malwa. There was Mohammed Ali Rogay, a Konkani Muslim, who

was a ‘Nakhuda’ or ship-owner/ captain. They were joined by the Goan

Catholic Rogério de Faria, who had connections with the Portuguese

authorities that controlled the port at Daman. Initially, the existence

of Daman was a thorn in the side of the British who tried to restrict

the export of opium through Bombay alone. They eventually gave up and

settled for taxing the produce at its source.

The second act of Jejeebhoy’s life can be seen as both a continuation of his earlier life and a sharp break from it. When his son Cursetjee was old enough, Jejeebhoy began to step back from the business to focus on civic life. While opium was seen as just another item of trade within these mercantile circles, it is possible that Jejeebhoy wanted to distance himself publicly from the drug trade. Opium prices were freely published in newspapers and it was clear that none of the merchants felt any sympathy for the Chinese when the First Opium War broke out. Jejeebhoy and the others seemed to be primarily interested in compensation for destroyed stocks and for regular trade to resume. But in his burgeoning career as a public figure, he might have been worried about the potential damage to his reputation.

Various historians have noted that between European merchants and

their Indian counterparts there was a sense of shared community and

mutual respect. But that was definitely not the case between the

citizenry and the government in the Bombay Presidency. The Parsis,

meanwhile, had repeatedly expressed their loyalty to the British and

were rapidly becoming the most Anglophile of all Indian communities. For

them and the other elite of Bombay, charity and public works were a way

of building a common moral and ethical ground with the British — a way

of proving their shared humanity. Simultaneously, the British were

looking to ensure that the local elites saw a common interest in

continued British rule.

Various historians have noted that between European merchants and

their Indian counterparts there was a sense of shared community and

mutual respect. But that was definitely not the case between the

citizenry and the government in the Bombay Presidency. The Parsis,

meanwhile, had repeatedly expressed their loyalty to the British and

were rapidly becoming the most Anglophile of all Indian communities. For

them and the other elite of Bombay, charity and public works were a way

of building a common moral and ethical ground with the British — a way

of proving their shared humanity. Simultaneously, the British were

looking to ensure that the local elites saw a common interest in

continued British rule.

At the forefront of this push to use philanthropy to forge bonds with the rulers was Jejeebhoy. His donations were prolific. By 1855, his commercial empire was mostly complete and he had devoted himself entirely to philanthropy and public life. In his biography, historian J.R.P. Mody calculates that Jejeebhoy would have donated £2,450,00 over the course of his life. In current terms, that would be around £10 million or ₹100 crore.

This astronomical charity left its mark on Bombay and Pune. He paid two-thirds of the entire cost of the Pune waterworks, with the remainder coming from the government. His wife, Avabai, single-handedly paid for the entire construction of the Mahim causeway that connects the island of Mahim to Bandra and ensured that the government wouldn’t charge citizens a toll.

He founded the Sir JJ School of Art, where John Lockwood Kipling, father of Rudyard Kipling, would be dean in the 1860s. Probably the most notable of all his contributions was the founding of JJ Hospital, to which he eventually donated both land and a large sum of money.

Caste and class lines

The hospital had been entirely Jejeebhoy’s idea and when he wrote to

the British government, they responded to the idea enthusiastically. But

the process became extremely drawn out when sharp differences emerged

in ideas of how the hospital should function. Jejeebhoy wanted it

designed around class and caste lines, but the government refused.

Finally, when the hospital was built, some concessions were made, like a

separate kitchen for Brahmins.

The hospital had been entirely Jejeebhoy’s idea and when he wrote to

the British government, they responded to the idea enthusiastically. But

the process became extremely drawn out when sharp differences emerged

in ideas of how the hospital should function. Jejeebhoy wanted it

designed around class and caste lines, but the government refused.

Finally, when the hospital was built, some concessions were made, like a

separate kitchen for Brahmins.

With his philanthropy, Jejeebhoy’s reputation among the British was growing. In 1834, he became one of the first Indians appointed as Justice of the Peace, which was a position in the Court of Petty Sessions, the de facto municipal authority. In 1842, he became the first Indian to be knighted, officially receiving a Sir prepended to his name.

But Jejeebhoy wasn’t done. In secret, he began a campaign to receive a hereditary title. As Palsetia writes, it was the first “organized programme of publicity on behalf of a colonial subject”. Thomas Williamson Ramsay, former revenue commissioner of Bombay, wrote a glowing account of his numerous good deeds and with the help of many well-wishers, this account was widely distributed among the Lords of England, even reaching the hands of Prince Albert himself. In 1856, a profile of Jejeebhoy was published in The Illustrated London News. The campaign was eventually successful.

In 1857, Queen Victoria named him the first Baronet of Bombay. But it took four years for him to finally obtain the title because the British government remained unsure of Parsi inheritance law and whether it would complicate the inheritance process. To secure the baronetcy, Jejeebhoy had to place a property (officially referred to as Mazagaon Castle) and a sum of ₹25 lakh in trust.

Baronetcies galore

Now that Jejeebhoy had blazed the trail, the British eventually opened up the honours system to colonial subjects. They used the gesture to portray a united and homogeneous global empire. Between 1890 and 1911, seven baronetcies were granted to citizens of the Bombay Presidency and 63 Parsis were knighted by 1946. Despite being such a small community, various Parsis would endow more than 400 educational and medical institutions over the course of the 19th and early 20th centuries.

It’s apparent that Jejeebhoy’s philanthropy, institution-building and public works improved countless lives. But at the same time, the sheer wealth that he and other members of his class accumulated allowed them to negotiate colonialism and even benefit from it in a way that was impossible for most ordinary citizens. In the 160 years since Jejeebhoy’s death in April 1859, we still wrestle with his complicated legacy.

The writer is an award-winning playwright and freelance journalist based in Chennai. Twitter: @notrueindian

When Jejeebhoy met him, Jardine’s time as a doctor of the East India Company was almost at an end. He had plans to set up a trading house in Canton, now known as Guangzhou. That trading house still exists, as a conglomerate with a market capitalisation of more than $40 billion. Jardine’s firm would become so enormously successful because it was soon going to corner the market on one particular commodity, one that was much more profitable than cotton, and one whose demand was exploding because the British had got millions of Chinese hopelessly addicted to it: opium.

Opium wasn’t just another trade good for the British Empire. It was the necessary corollary to another commodity: tea. The British were importing tens of millions of pounds of tea from China every year. There seemed to be no end to the demand and everyone involved was making huge profits. There was just one problem. They didn’t have the cold hard cash or rather, cold hard silver to pay for it.

JJ Hospital, named after founder Jamsetjee Jejeebhoy. | Photo Credit: Special Arrangement

Shipped from Bombay

The opium came from the East India Company’s nearby colony, India. It was grown in Malwa and shipped from Bombay. At its height, almost one-third of the entire trade was going to one firm, Jardine’s trading house in Canton. And the man who enabled this trade from India was becoming stunningly wealthy.

By the time he was 40, Jamsetjee Jejeebhoy had allegedly made more than ₹2 crore — in the 1820s. He was already one of the richest men in the entire country, but he had his eye on even greater prizes.

The life of Jamsetjee Jejeebhoy makes for an excellent story. It neatly divides into two acts. In the first act, Jejeebhoy lives a life of adventure and daring. In the second act, he becomes an elder statesman, a civic figure working for the benefit of the community. This is no accident. Jejeebhoy’s ambitions were sophisticated and manifold. They would’ve been far out of reach for anybody who wasn’t willing to reinvent themselves. Even in his earliest days, there are signs that Jejeebhoy was conscious of his persona, taking steps to change details of his life to better fit his desired narrative.

Sir JJ School of Art founded by Jamsetjee Jejeebhoy. | Photo Credit: Vivek Bendre

His early life was marked by tragedy: he lost both his parents before the age of 16. His family was from a Parsi priestly community but his father worked as a weaver. After they died, Jejeebhoy moved to Bombay and began working for his maternal uncle, buying and selling empty liquor bottles. He earned the nickname ‘Batliwalla’ or bottle-seller and seemed to revel in it, often signing letters with the moniker as if it actually was his last name.

At 20, he married his maternal uncle’s daughter, Avabai, who was around 10 years old at the time. And through his family, he began to trade, making five trips to China. None of these trips directly made him rich, but they did make him vital connections across South and East Asia, including, of course, William Jardine.

Vital connections

A sketch of the First Opium War. | Photo Credit: Getty Images

The second act of Jejeebhoy’s life can be seen as both a continuation of his earlier life and a sharp break from it. When his son Cursetjee was old enough, Jejeebhoy began to step back from the business to focus on civic life. While opium was seen as just another item of trade within these mercantile circles, it is possible that Jejeebhoy wanted to distance himself publicly from the drug trade. Opium prices were freely published in newspapers and it was clear that none of the merchants felt any sympathy for the Chinese when the First Opium War broke out. Jejeebhoy and the others seemed to be primarily interested in compensation for destroyed stocks and for regular trade to resume. But in his burgeoning career as a public figure, he might have been worried about the potential damage to his reputation.

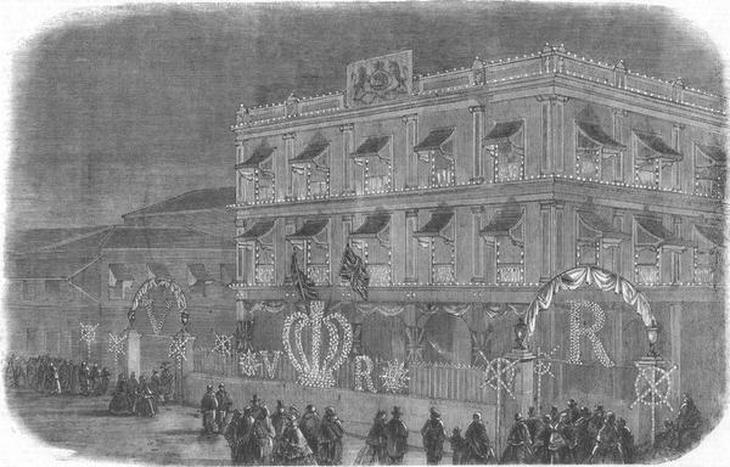

An illustration of Jamsetjee Jejeebhoy’s Bombay residence in ‘The Illustrated London News’, 1858. | Photo Credit: Wiki Commons

At the forefront of this push to use philanthropy to forge bonds with the rulers was Jejeebhoy. His donations were prolific. By 1855, his commercial empire was mostly complete and he had devoted himself entirely to philanthropy and public life. In his biography, historian J.R.P. Mody calculates that Jejeebhoy would have donated £2,450,00 over the course of his life. In current terms, that would be around £10 million or ₹100 crore.

This astronomical charity left its mark on Bombay and Pune. He paid two-thirds of the entire cost of the Pune waterworks, with the remainder coming from the government. His wife, Avabai, single-handedly paid for the entire construction of the Mahim causeway that connects the island of Mahim to Bandra and ensured that the government wouldn’t charge citizens a toll.

He founded the Sir JJ School of Art, where John Lockwood Kipling, father of Rudyard Kipling, would be dean in the 1860s. Probably the most notable of all his contributions was the founding of JJ Hospital, to which he eventually donated both land and a large sum of money.

Caste and class lines

The special postage stamp issued in April 1959 to commemorate Jejeebhoy’s death anniversary. | Photo Credit: Getty Images/ iStock

With his philanthropy, Jejeebhoy’s reputation among the British was growing. In 1834, he became one of the first Indians appointed as Justice of the Peace, which was a position in the Court of Petty Sessions, the de facto municipal authority. In 1842, he became the first Indian to be knighted, officially receiving a Sir prepended to his name.

But Jejeebhoy wasn’t done. In secret, he began a campaign to receive a hereditary title. As Palsetia writes, it was the first “organized programme of publicity on behalf of a colonial subject”. Thomas Williamson Ramsay, former revenue commissioner of Bombay, wrote a glowing account of his numerous good deeds and with the help of many well-wishers, this account was widely distributed among the Lords of England, even reaching the hands of Prince Albert himself. In 1856, a profile of Jejeebhoy was published in The Illustrated London News. The campaign was eventually successful.

In 1857, Queen Victoria named him the first Baronet of Bombay. But it took four years for him to finally obtain the title because the British government remained unsure of Parsi inheritance law and whether it would complicate the inheritance process. To secure the baronetcy, Jejeebhoy had to place a property (officially referred to as Mazagaon Castle) and a sum of ₹25 lakh in trust.

Baronetcies galore

Now that Jejeebhoy had blazed the trail, the British eventually opened up the honours system to colonial subjects. They used the gesture to portray a united and homogeneous global empire. Between 1890 and 1911, seven baronetcies were granted to citizens of the Bombay Presidency and 63 Parsis were knighted by 1946. Despite being such a small community, various Parsis would endow more than 400 educational and medical institutions over the course of the 19th and early 20th centuries.

It’s apparent that Jejeebhoy’s philanthropy, institution-building and public works improved countless lives. But at the same time, the sheer wealth that he and other members of his class accumulated allowed them to negotiate colonialism and even benefit from it in a way that was impossible for most ordinary citizens. In the 160 years since Jejeebhoy’s death in April 1859, we still wrestle with his complicated legacy.

The writer is an award-winning playwright and freelance journalist based in Chennai. Twitter: @notrueindian

No comments:

Post a Comment