madrascourier.com

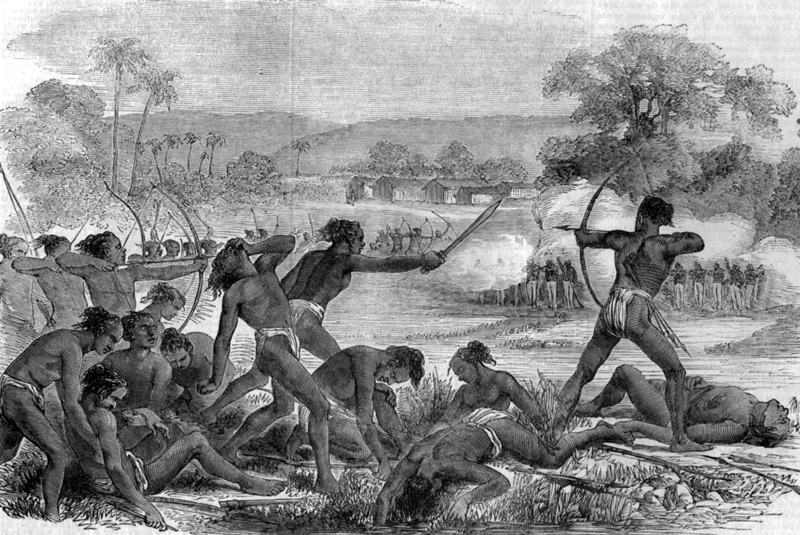

Tilka led the first tribal revolt against the British, fighting against the amoral seizure of historically Santhal lands.

Introduction

The Pax Britannica is so firmly established that the idea

of overt rebellion is always distant from our minds, even in a remote

State like Bastar.

– B. P. Standen, Chief Secretary to the Chief Commissioner, Central Provinces, 1910

1

In February of 1910 the tribal population of the princely

state of Bastar in eastern India rose in rebellion against a small

British force stationed within the kingdom. This event, referred to as

bhumkal (earthquake), established Bastar as a major battleground for tribal (

adivasi)

2

revolt during the colonial period. Almost exactly 100 years later,

in April 2010, 76 members of the Indian Central Reserve Police Force

were ambushed and massacred by Naxalite rebels, most of them

adivasis, in the thick jungles of the Bastar region.

3

The puzzling fact about Bastar, however, is that unlike so many

other regions of India beset by tribal conflict, it never came under the

direct control of the British during the colonial period.

A large body of historical literature has documented how British colonialism gave rise to widespread rural unrest in India.

4

During the course of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries there

was a major increase in the number of tribal revolts throughout the

country. Kathleen Gough has noted that ‘British rule brought a degree of

disruption and suffering among the peasantry which was, it seems

likely, more prolonged and widespread than had occurred in Mogul times.’

5

Ranajit Guha writes, ‘For agrarian disturbances in many forms and

on scales ranging from local riots to war-like campaigns spread over

many districts were endemic throughout the first three quarters of

British rule until the very end of the nineteenth century.’

6

Along these lines, scholars have shown how new colonial policies,

such as the commandeering of forest lands and increased rural taxation,

led to widespread discontent and rebellion among indigenous groups. Eric

Stokes notes, for example, that ‘resentment against [moneylenders]

boiled over most readily into violence among tribal people like the

Bhils, Santals, and . . . the Gonds’.

7

Historians have also shown that after independence, the new Indian

government did not reform a number of colonial-era policies, especially

those dealing with forestry,

8

and tribal conflicts continued to occur throughout the country,

especially in former areas of direct British rule like Bengal, Bihar,

and Jharkhand. The Naxalite movement became the main vehicle for tribal

revolt in contemporary India.

But the fact that Bastar, a former princely state ruled by

a Hindu dynasty, was one of the epicentres of tribal violence poses a

major challenge for the literature linking colonialism and contemporary

conflict.

9

Although the British did exert final authority over the native

states, princes often had large amounts of internal discretion within

their territories, and these kingdoms—at the very least—featured less of

a colonial footprint. Why then has Bastar experienced such intense

periods of tribal rebellion—both in the colonial and post-colonial

period?

This article makes two central arguments in offering

answers to these questions. First, using a wide array of primary source

material, I demonstrate that during colonialism, tribal conflict began

in Bastar precisely because of increasing

British influence in the state. Three specific policies were implemented

in Bastar that engendered tribal revolt: colonial officials took direct

control over the forests, they displaced tribals from their land, and

they heavily interfered in succession to the throne, which upset the

native population. Second, I show that the post-independence Indian

government continued—often in uncannily similar ways, as I detail—most

of the same colonial-era policies in the region that had initially led

to tribal uprisings. These decisions in Bastar led to the rise of the

contemporary Naxalite insurgency, which is only the latest incarnation

of tribal unrest in the region. The case of Bastar, therefore, reaffirms

the central role of British colonialism in producing tribal conflict in

India by showcasing its effects even in areas that never formally came

under the ambit of direct rule. Importantly, however, the continuing

violence in Bastar concurrently implicates the post-colonial government

in failing to end the root causes of the bloodshed.

Despite its remote location, the political developments in

colonial Bastar that led to persistent rebellion provide important

insights for other states throughout Asia. The British practice of

retaining areas of indirect rule within a colony was taken from India

and exported to later colonial territories such as Burma and Malaya.

10

Therefore, understanding contemporary violence in other

post-colonial states in Asia—ethnic separatism throughout former areas

of indirect rule in Myanmar, for example—can be informed by analysing

what first transpired in Bastar.

This article contains four major sections. In the first

two, I discuss the general history of tribal revolt in colonial and then

post-colonial India. In the final two, I examine these broad trends

within the kingdom of Bastar, again in the colonial and post-colonial

periods.

Tribal revolts in British India and the princely states

Colonial rule in India produced several new policies that

had deleterious consequences for the indigenous population of the

country. In the broadest sense, the British approached the jungles with

an overarching goal of bringing ‘primitive’ peoples under the control of

a modern, centralized bureaucracy.

11

This led to the official classification of tribal populations—a

chief example was the institution of the Criminal Tribes Act in 1871,

which sought to control the movement of certain tribes with a history of

criminal activity.

12

But under the Act all members of a designated tribe were considered

criminals, even if they had never committed a crime, which led to

widespread social stigmatization.

Another major change dealt with forest policies and tribal

land displacement. Colonial rule marked the first time in Indian

history that a government claimed a direct proprietary right over

forests.

13

This was something the preceding Mughals, for example, had not done.

14

The British state became the conservator of forests when it passed

the Indian Forest Act of 1878. Hundreds of thousands of acres of forest

lands that

adivasis had used unfettered for

centuries were suddenly kept in reserve, a practice that did not change

for the rest of the colonial period.

15

With British control of the forests came the concomitant rise of

moneylenders, traders, and immigrants, and the influx of these new

intermediary groups led to widespread

adivasi land displacement.

16

These are only some of the major changes instituted during the

colonial period; myriad smaller developments—such as the introduction of

money rather than a barter economy—also transformed the nature of

tribal society during the course of British rule.

Consequently, revolts among the indigenous population

became a routine occurrence during colonialism, especially in the

nineteenth century. For instance, in 1855 the Santhals rebelled; in 1868

the Naikdas; in 1873 the Kolis; and in 1895 the Birsas. This is only a

small smattering of the total number of conflicts. Guha has documented

over 110 different colonial-era peasant revolts,

17

and Gough records at least 77 since the advent of British rule.

18

Colonial administrators, however, only directly governed

three-quarters of the population of India; the remainder lived in

semi-autonomous princely states. These areas did not experience nearly

the same level of tribal discontent or conflict. Despite having a

reputation as feudal autocrats, many princes pursued liberal policies

towards the same tribal groups that rebelled in British India. In

Rajputana, for example, both the Bhil and Mina tribes were incorporated

into the structure of the princely government because Rajput leaders

recognized them as the original inhabitants of the land. These tribes

were also charged with ceremonially placing the

rajatilaka

(a red powder mark used during the coronation process) on the brow of

the newly crowned king. In Jaipur, the Minas were designated the

guardians of the royal treasury.

19

In Travancore and Cochin, tribal groups were given ownership of

their land, government subsidies to improve it, and were shielded by

special policies that limited the imposition of the outsiders who were a

major problem for

adivasis throughout British India.

20

In Jammu and Kashmir, many members of the Bakkarwal tribe were employed as tax collectors (

zaildaars) and became an important part of the Dogra government.

21

In 1942, most of the rulers of the Eastern Feudatory States

approved a draft policy (although it was not implemented) declaring that

tribal groups ought to be the first claimants to forest lands and

should also have the right to be governed by independent

panchayats (village councils).

22

Princes displayed much more tolerance for tribal groups, and

adivasis

fared better under their rule than that of British administrators in

the provinces. The same encroachments on tribal society that occurred in

British India were largely absent in the princely states; as Verrier

Elwin, famed anthropologist of Indian

adivasis,

summarized the situation, it was ‘most refreshing to go to Bastar from

the reform-stricken and barren districts of the Central Provinces’.

23

Tribal revolts in contemporary India: the Naxalite conflict

Tribal revolts did not end once India gained independence

in 1947, and in some parts of the country they became endemic. In the

broadest sense, the new government did not end a number of colonial

policies that were the cause of tribal revolts—in fact, it exacerbated

the situation. For example, in comparing British and post-1947 forest

policy, Ramachandra Guha notes: ‘The post-colonial state has taken over

and

further strengthened the organizing

principles of colonial forest administration—the assertion of state

monopoly right and exclusion of forest communities.’

24

Richard Haeuber similarly writes: ‘Despite the transition from

colonial to independent status, forest resource management changed

little: exclusionary processes

accelerated . . . to consolidate state authority over forest resources.’

25

Consequently, tribal conflict continued into the

post-independence era, and the Naxalite movement became the face of

contemporary rebellion. Though no one knows the precise constitution of

the various Naxalite cadres, it is widely believed that the majority of

members come from poor tribal groups such as Scheduled Tribes.

26

Scheduled Castes are also involved in the movement. In the most general terms, Naxalites are poor peasants.

27

Brutal poverty and landlessness has historically been a major

problem among these groups, and the present Naxalite leadership has

successfully mobilized them around these grievances. Home Secretary G.

K. Pillai confirmed in a 2009 speech that the government and its

policies were largely to blame for the rise of Naxalism.

28

The term ‘Naxalite’ encompasses several different

communist militant groups operating guerrilla campaigns in various parts

of the country. These movements are not necessarily working in tandem

with one another. One of the historic and regional strongholds of the

Naxalites is the former British areas of West Bengal and Bihar. Naxal

insurgents also operate in Orissa, Chhattisgarh, and Andhra Pradesh (the

‘Red Corridor’), and have been active as far south as the Malabar

regions of Kerala. By some rough estimates, Naxalite cadres are

currently functioning in roughly 180 out of India's 631 districts.

The Naxalites come from the long and complicated history

of the communist movement in India. The Communist Party of India

abandoned violent revolution and adopted parliamentary politics in 1951,

which subsequently led to the creation of a splinter faction, the

Communist Party of India, Marxist. In 1967 another split occurred and

the far-left Communist Party of India, Marxist-Leninist was established.

Most contemporary Naxalite groups originate from the Communist Party of

India, Marxist-Leninist. These groups are Maoist, drawing on the

tactics of Mao Zedong's insurgency during the Chinese Civil War.

There are generally considered to be three historical

phases in the Naxalite movement. During the first, from 1967 to 1975,

the campaign began in West Bengal and spread to the surrounding regions.

The beginning of the conflict is dated to an uprising of peasants

against landlords in 1967 in the West Bengali village of Naxalbari

(providing the name of the movement). The uprising was led by former

Communist Party of India, Marxist member Charu Majumdar—the nominal

founder of the Naxalites—and most of the peasants involved in the revolt

belonged to the Santhal tribe. By 1975 the initial rebellion was

effectively stamped out. Then, from 1975 until the early 2000s, the

various Maoist groups became severely fragmented and had limited success

in carrying out attacks against the Indian government. Beginning over

the last decade, however, the movement reorganized successfully under

new leadership and has now come to pose a major threat to Indian

political stability. The culmination of the rebirth of the movement came

in 2004 when two of the largest Naxalite factions, the People's War

Group and Maoist Communist Centre, joined together to form the Communist

Party of India, Maoist. In 2006 Prime Minister Manmohan Singh stated

that Naxalites were ‘the single biggest internal security challenge ever

faced by our country’.

29

He later also admitted that the Government of India was losing the war against them.

30

Naxalites were estimated at one point to control one-fifth of the land mass of India.

31

In many of these swaths of territory they operate parallel

governments, grouping together villages into new districts, selecting

administrators, and setting up police stations, schools, and even courts

where oppressive landlords and moneylenders suffer retribution. The

insurgents are said to be armed with advanced weaponry such as AK-47s,

improvised explosive devices, and even solar panels to charge electrical

equipment. Their attacks are sophisticated, well-organized, and

extremely deadly.

32

The rebels are also aided in that they operate in the deepest parts

of India's jungles, areas which are often impossible to visit. In

Bastar, for example, as far back as 1881 the deputy superintendent of

the census for the Central Provinces wrote to his superiors that ‘there

is little prospect of a Census being possible [in Bastar]’ and also

noted that the figures from 1871 were ‘manifestly incorrect’.

33

Even today, travelling from Jagdalpur, the capital of Bastar district, to its surrounding villages can be difficult.

The violence in the Naxalite insurgency has been immense

over the past several years. According to conflict data from the

Worldwide Incidents Tracking System,

34

which is operated by the National Counterterrorism Center, 1,920

people died from Naxalite violence during the years 2005–2009, while

another 1,412 were wounded. The Indian government has responded to this

movement via a massive anti-terrorism campaign, begun in November 2009,

in which over 50,000 troops are involved (Operation Green Hunt). The

Naxalites, however, have continued their attacks relentlessly.

Given that princely rulers often enforced liberal policies towards adivasis,

and that the Naxalite movement began and is still strongest in former

areas of direct British rule, what accounts for the immense historical

conflict in Bastar? How is it that this small and isolated princely

kingdom became ground zero for tribal violence in both colonial and

post-colonial India?

British influence and tribal revolt in Bastar

The former Bastar kingdom is located in the state of

Chhattisgarh. During the British period Bastar was over 13,000 square

miles, or roughly the size of Belgium. It had a population, in 1901, of

306,501.

Adivasis constituted the largest

segment of the population, and Gonds were the major tribe inhabiting the

area. The state was governed by a lineage of Hindu kings who were not

adivasis

themselves but Rajputs. The founders of the Bastar state were,

according to legend, driven from their former home in Warangal by Muslim

invaders in the fourteenth century. They then settled in Bastar and

became high priests of the goddess Danteshwari, whom the tribes of

Bastar worshipped. The princely state was known for its unique

celebration of the Dasera festival. The raja is ‘abducted’ by tribals on

the eleventh day of Dasera and then returned to the throne the next

day, a ritual that symbolizes the close linkage between the

adivasis and their king.

35

During the pre-colonial period, Bastar had been

incorporated as part of the Mughal and then Maratha empire. Due to its

rough terrain and geographical inaccessibility, however, it always

retained a certain level of isolation—Deputy Commissioner of the Central

Provinces and Berar Wilfrid Grigson remarked that Bastar was a

‘backwater in Indian history’.

36

The entire region is one of the most heavily forested areas in

India (it is the site of the Dandakaranya forest), and colonial

officials often referred to Bastar as one of a number of ‘jungle

kingdoms’.

When the British finally broke Maratha power in central

India in 1818 they subsequently began to enter into a political

relationship with Bastar (a former tributary state of the Marathas), and

in 1853 the kingdom officially came under the system of British

indirect rule. Bastar State was included as part of the Central

Provinces administration.

The British immediately began to interfere in Bastar's

administration in three ways: by implementing new forest policies,

displacing tribals from their land, and heavily interfering in

succession to the throne—that is, removing rajas and replacing them with

compliant officials. At first, this interference in the state came

under the pretext of preventing human sacrifice. An official inquiry in

1855, however, showed that human sacrifice was not a local tradition.

The reporting officer wrote that it was ‘pleasing to find that there did

not exist . . . a tradition of human sacrifices. In the low country it

was said that these hill tribes never sacrificed human beings and for

once the account was strictly true.’

37

A more likely cause of intervention was the fact that Bastar had

extremely large iron ore deposits, as well as other precious minerals,

timber, and forest produce.

38

Over time, British influence in Bastar increased—beginning first

with forest administration—due to efforts to appropriate its natural

resources, and by 1876 colonial administrators effectively governed the

state, the raja ruling in name only.

Colonial influence bred rebellion in Bastar. The state

experienced two important tribal revolts during colonialism, in 1876 and

1910.

39

The cause of the first rebellion was trivial enough—the arrival of

the Prince of Wales to India. The diwan of Bastar attempted to arrange a

meeting between the prince and the raja. The

adivasis,

however, interpreted this as an attempt by the British to abduct the

raja, and within hours they mobilized in large numbers and prevented him

from leaving the state. Though traditionally referred to as a

rebellion, the conflict in reality was relatively minor and featured

little bloodshed. W. B. Jones, chief commissioner of the Central

Provinces, summarized the incident in a confidential report from 1883:

In March of 1876 a disturbance broke out at Jugdalpur, the

origin of which has never been quite satisfactorily explained. The

immediate occasion of the outbreak was the Raja's setting out for Bombay

to meet . . . The Prince of Wales. The people assembled in large

numbers and compelled him to return to Jugdalpur. Their ostensible

demand was not that he should not go, but that he should not leave

behind the then Diwan Gopinath Kapurdar (a Dhungar, shepherd by caste)

and one Munshi Adit Pershad (a Kayeth in charge of the Raja's Criminal

Court), whom the people charged with oppression . . . They simply

demanded that the two men mentioned above should be sent away.

40

Were the

adivasis rebelling

against the raja? The British themselves were sceptical. An officer sent

to investigate disconfirmed the idea, noting that ‘Relations between

Raja and subjects generally [were] good, very good.’

41

Commissioner Jones also noted that ‘the insurgents committed no violence and professed affection for the Raja’.

42

At worst, the

adivasis were upset with the

raja's choice of appointees. But another central cause of the

disturbance was creeping British influence in the state—for example,

Jones made sure to note that the

adivasis earlier in the year had reacted very negatively to new Christian missionaries who had arrived in the kingdom.

43

A number of new colonial policies combined to create a rising sense of embitterment among the tribal population.

After the death of Raja Bhairam Deo in 1891, the British

began to penetrate the princely administration ever more steadily. As

the raja's son, Pratap Deo, was only six years old at the time, the

British directly administered the state for the next 16 years. During

eight of these years the state was even governed by Englishmen. This

direct control over Bastar in reality also continued after Pratap Deo

became raja in 1908. Extra Commissioner Rai Bahadur Panda Baijnath acted

as superintendent during the last four years of Pratap Deo's minority,

and then continued to act as diwan after the raja finally took the

throne. E. A. De Brett, officer on special duty in Bastar, wrote about

Pratap Deo's lack of power, noting that he was ‘bound in all matters of

importance to follow the advice of his Diwan and has never taken an

active part in State affairs’. The chief commissioner of the Central

Provinces concluded later that ‘the Diwan was the virtual ruler of the

State’.

44

The 1910 rebellion was much more violent and widespread

than its predecessor. One of the chief instigators of the conflict was

Lal Kalendra Singh, the first cousin of the raja and a former diwan

himself. He had been angling for a return to power after he had been

removed by the British due to ‘incompetence’. He mobilized the adivasis

by declaring that if he was returned to the throne he would drive the

British out of Bastar completely. A contemporary report from a Christian

missionary living in Bastar, Reverend W. Ward, sheds some light on the

rebellion:

In the second week of February we first heard of the

unrest among the Aborigines south of Jagdalpur. Vague rumours were

afloat but none of a very serious nature. On the 18th a Christian living

among the Prajas—Aborigines—came to me with the story that the Prajas

were all armed and were moving toward Keslur, where the Political Agent,

Mr. E. A. De Brett, I.C.S., was camping, to make known their grievances

. . . A branch of a mango tree, a red pepper, and an arrow were tied

together, and sent to all villages in the State. The mango leaves stand

for a general meeting; the red pepper, a matter of great importance is

to be discussed and that the matter is necessary and urgent; the arrow, a

sign of war.

45

The entire state rose in revolt and the existing British

force of only 250 armed police was quickly overwhelmed. For weeks

looting, robbery, and arson plagued the entire kingdom. By the end of

February additional troops from Jeypore and Bengal had arrived and the

rebellion was finally put down. Hundreds of prisoners were taken,

including Lal Kalendra Singh, who was expelled from the state and later

died in prison.

The British conducted several inquiries into the causes of

the 1910 rebellion. The chief commissioner of the Central Provinces

summarized the British government's position in a December 1910 report

that stated:

from an examination of the evidence before them the Government of India were of opinion that a

too zealous forest administration might not improbably be the main cause of the discontent of the hill-tribes.

46

De Brett also conducted an inquiry on the rebellion and

discerned 11 main causes, ranking chief among them ‘the inclusion in

reserves of forest and village lands’.

47

Prior to colonialism, the rajas that ruled Bastar did not reserve forest lands, giving

adivasis almost unrestricted access to these areas.

48

Alfred Gell notes that prior to the arrival of British

administrators ‘the tribal population [in Bastar] enjoyed the benefit of

their extensive lands and forests with a degree of non-exploitation

from outside which would hardly be matched anywhere else in peninsular

India’.

49

Nandini Sundar similarly highlights that prior to British rule there was not even a recorded forest policy for the kingdom.

The colonial state began reserving forests in Bastar in

1891, especially areas rich in various kinds of forest produce. This

meant timber most of all, but also a class of items known as non-timber

forest product, which included rubber, medicinal plants, berries, and

tendu leaves, used for rolling tobacco. Due to this new reservation policy, entire

adivasi

villages in reserved areas were forcibly moved by colonial authorities.

Corporations, like those involved in the timber trade or iron mining,

entered areas where

adivasis had lived and were granted a monopoly right over forest produce. Once a forest area was officially reserved,

adivasis no longer had any claim to these lands and were charged fees for collecting produce or grazing in these areas.

50

L. W. Reynolds, another officer stationed in Bastar, noted the

singular importance of this policy of forest reservation in promoting

rebellion:

The proposal to form reserves was not finally sanctioned

until June 1909 and action giving effect thereto must therefore be

nearly synchronous with the rising. In his telegram of the 17th March

1910 the Chief Commissioner stated that one of the objects of the rising

was the eviction of foreigners. I believe it to be the case that in

connection with the exploitation of the forests Messrs. Gillanders,

Arbuthnot and Company, who have a contract in the State, have introduced

a large number of workmen from Bengal . . . the [tribes] resent the

introduction of these foreigners. It is not unnatural.

51

All of the contemporary reports pointed to the same causes—foremost, new forest policies that displaced

adivasis

from their land. Sundar also found that the main participants in the

1910 rebellion were from areas that suffered the most under new colonial

land revenue demands.

52

Despite the admission to an ‘overzealous’ forest administration,

British policy in Bastar did not change substantially in the wake of

rebellion. They continued to sign various forest mining agreements or

renewals of previous agreements—in 1923, 1924, 1929, and 1932. The 1923

agreement, for example, renewed a licence for Tata Iron and Steel to

mine Bastar's ‘enormous reserves of iron ore’.

53

Forest lands also continued to be reserved. As late as 1940 the

administrator of Bastar State wrote to the political agent of

Chhattisgarh States that ‘Most of them [

adivasis]

dislike the proposals for forest reservation . . . However if these

areas are not reserved it will be impossible to reserve any good teak

forests in the Zamindari.

(It is a most unfortunate

fact that the best teak areas and the thickly populated, well cultivated

Maria [Gond] villages coincide).’

54

Aside from new forest policies, the British also continued

to directly govern the state through various machinations, although

this, too, had been disastrous in 1910. In 1922 Rudra Pratap Deo died

without a male heir, and his daughter, Profulla Kumari Devi, was placed

on the throne as a child. One British administrator noted: ‘She is about

eleven years of age and no reference is made as to her eventual fitness

to rule, but this is unimportant as she could always rule through a

Manager or Dewan.’

55

Bastar therefore experienced yet another minority administration.

Then, in 1936, when the Maharani of Bastar died suddenly of surgical

complications in London, the British installed her eldest son, Pravir

Chandra Bhanj Deo, on the throne, although he was only seven years old

at the time. The Maharani's husband, Raja Prafulla Bhanj Deo, who was

the first cousin of the ruler of the nearby Mahurbhanj State, had been

passed over as a possible successor. This was an attempt to continue

directly ruling the state instead of turning over power to the queen's

consort. In fact, colonial administrators in charge of the guardianship

of Pravir Chandra were themselves confused as to the justification

behind his minority administration. Administrator E. S. Hyde commented:

I am not altogether clear what is meant in this case by

guardianship . . . It would, however, be of assistance to me and my

successors if our position could be defined. It is certainly an unusual

and somewhat delicate one, for normally when a Chief is a minor his

father is dead.

56

R. E. L. Wingate, joint secretary to the Government of

India, Foreign and Political Department, noted that passing over

Prafulla for the throne was against the queen's wishes:

It is her [the Maharani’s] desire that Profulla should

have the title of Maharaja and that he should share her role as Ruling

Chief, being co-equal with her and succeeding her as Ruler in the event

of her death before him, her son not succeeding to the

gaddi [throne] until his death.

57

Despite this, Prafulla—who had been educated and gained

high marks at Rajkumar College in Raipur—was deemed ‘exceedingly vain

and filled with self-conceit . . . he is a man of very questionable

moral character and completely unstable’

58

and was denied the throne. Prafulla had also been very popular with

tribal groups in Bastar. E. S. Hyde noted a meeting between

adivasis and Prafulla in 1936 after he had been passed over for control of the kingdom:

First of all the Mahjis told Prafulla that they had

confidence and trust in him and that he was their ‘mabap’ [mother and

father]; to this he replied that he could do nothing for them, that he

had no powers. He was willing to do anything for them but . . . he could

do nothing.

59

Even before the death of the maharani in 1936 there had

been a movement to install Prafulla as the hereditary raja, in ‘joint

rulership’ of Bastar with his wife; later came an attempt to at least

establish a council of regency and make him the regent.

60

Both movements were squashed by the British. They believed that

Prafulla was responsible for several anti-British pamphlets that had

appeared over the past several years in newspapers throughout India.

Administrators noted, however, that ‘there is no actual proof as the

printer's name is absent from the pamphlets’.

61

The British eventually even removed Prafulla as the guardian of his

children and deemed that he should not be allowed to enter Bastar

State.

62

The British found fault with almost all of the occupants

of the throne of Bastar, and managed to have them removed from power in

order to clear the way for direct colonial administration of the

kingdom. Lal Kalendra Singh was removed as diwan because colonial

authorities came to realise he was ‘totally unfit to be trusted with any

powers’.

63

Rudra Pratap Deo was a ‘very weak-minded and stupid individual . . . considered unfit to exercise powers as a Feudatory Chief’.

64

Prafulla Bhanj Deo was an agitator, unstable, and needed to be kept

away from his own children. And by the dawn of independence, colonial

administrators were already beginning to have serious doubts about the

abilities of his son, Pravir Chandra, who was heir to the Bastar throne.

The colonial history of Bastar after the mid nineteenth

century featured British officials taking control over forest lands,

displacing tribals, and finding ways to govern the state directly rather

than through native rajas supported by the local population. All of

these factors increased unrest among the adivasis of Bastar and led to two tribal rebellions against British rule.

Tribal revolt in contemporary Bastar: the rise of the Naxalites

After independence, Pravir Chandra was removed as the

official ruler of Bastar, and was relegated to a ceremonial position. He

retained his title as the raja of Bastar, as well as his personal

fortune. Bastar State then acceded to the Central Provinces and Berar in

1948 and became part of the new state of Madhya Pradesh in 1950.

Despite the history of tribal revolt in the region, the

new Indian government did not reverse many policies inherited from the

erstwhile British administration. Foremost among them was colonial

forest policy: just as the inclusion of forest and village lands as

reserves was the major cause of pre-independence rebellions, the

post-independence government continued and even exacerbated this policy.

From 1956 to 1981, for instance, one-third of the total amount of

forest felled in Bastar District was for a variety of development

projects,

65

and land displacement among

adivasis in the

region continued to constitute a significant problem. Similarly, the

continuing influx of immigrants and traders exacerbated

adivasi

discontent; these groups, often with assistance from corrupt local

officials, were able to privately reserve forest and village lands, and

buy forest produce at below-market prices.

Exceptional insight into this continuing maltreatment of adivasis

even after independence comes from the writings of Devindar Nath, an

Indian Administrative Service officer and collector of Bastar District

in the 1950s. He notes how adivasis were often cheated out of their land, relating a story from 1955:

Each of the tenure-holders found himself in possession of

property worth several thousands of rupees, but in their ignorance and

illiteracy, they were neither conscious of their rights of property, nor

had they any realisation of its value. Timber merchants belonging to

different parts of the country made their appearance in the villages and

purchased timber from the Adivasis for small sums. Gangs of labourers

were employed to fell trees in the cultivators’ fields, and transport of

teak on a large scale started. The Adivasis were not paid even a small

fraction of the value of their teak . . . the stage was set for complete

denudation of the Adivasis’ fields.

66

Furthermore, just as another cause of colonial-era revolts

had been interference in succession to the throne of Bastar, the new

Congress government also continued this policy. They began agitating

against Pravir Chandra almost immediately after independence, exactly as

the British had done against the previous rulers of the state. From the

perspective of the Indian government, simply removing Pravir Chandra as

raja would have upset the large tribal population in Bastar. Instead,

they relied on the well-worn colonial policy of declaring as insane

those rulers whom they did not support. In a letter to Lord Curzon in

1899, Lord George Hamilton, secretary of state, explained this policy:

I felt that, if ever it became necessary to take so strong

a step as deposition [of a prince], you would be less likely to

frighten the Native Princes generally if you took that step, not on a

plea of misgovernment

but of insanity.

67

For instance, in 1920 Raja Rudra Pratap Deo was briefly

banned from entering his state when he returned from a trip abroad. The

main reason was because he, on three occasions, refused to meet with the

British Resident stationed in Bastar, which was considered a sign of

his instability. He apologized, stating that a family member of his had

been ill at the time. He was also surprised by the British overreaction.

68

The post-colonial Indian government attacked Pravir

Chandra for similar reasons. The first step came in 1953 when the Madhya

Pradesh government had the prince's property taken from him and placed

under the Court of Wards, which they argued was necessary because Pravir

Chandra was insane. The prince was, by most private accounts, an

enigmatic and bizarre man. His British caretakers noted that ‘he has

always been delicate’.

69

His father Prafulla considered him a ‘young puppy whom the British have ruined’.

70

Home Minister G. B. Pant once wrote in a letter to a Madhya Pradesh

minister: ‘Some people say that he was almost an idiot. I cannot say if

that is absolutely correct; but there is no doubt that he is erratic

and whimsical.’

71

But the Indian government also made numerous frivolous

claims against him. For example, the secretary of the Ministry of States

complained in May 1953 that ‘the Maharaja had now grown an enormous

beard and his hair had come down right up to his waist. The nails of his

fingers are very long. He looks just like a Sanyasi [renouncer] . . .

His is not a presentable appearance.’

72

About a subsequent meeting the secretary also wrote: ‘He [Pravir

Chandra] said that he has taken to the practice of Yogic exercises. I

suggested that he was too young for that and that he had better marry

and live a decent family life.’

73

Finally, he recounted a conversation with the raja in 1953:

I told the Maharaja that he had acted very improperly in

not paying due respect to the President of India when the latter had

visited that part of Madhya Pradesh. The Maharaja in reply disowned any

desire whatsoever to be disrespectful but said that his inability to be

present at the President's arrival was due to his illness. He was then

down with high fever.

74

Even the evidence of insanity the post-independence state

used mirrored that of the British—Pravir Chandra's refusal to meet the

president (legitimate or not), like that of his grandfather, was taken

as proof that he should be removed as ruler of Bastar.

Pravir Chandra was embittered by losing his property. In

1955 he formed the Adivasi Kisan Mazdoor Sangh (Tribal Peasants Workers'

Association), a political organization that was partly created to help

restore his land, but also pressed for better policies for villagers in

the state. In 1957 he was recruited by the Congress Party (apparently

despite the fact that he was insane) to stand for election. He viewed

this as another opportunity to have his property returned. However,

Congress would not relent and the shaky alliance quickly ended. After

that the Indian government began to work towards removing Pravir Chandra

from the Bastar throne, intending to replace him with his brother,

Vijay Chandra. In their internal memos they make a clear link to the

past in pursuing this line of action:

The adivasis have seen and read the articles appearing in

certain news-papers regarding the Maharaja's derecognition. They have

taken a serious view and are stirring up agitation . . . There was a

similar move at the time of the death of his grand-father Shri

Rudrapratap Deo and the adivasis stirred up a violent agitation, but the

British Government was wise enough to put his mother on the Gaddi.

History will repeat itself now.

75

Congress finally succeeded in removing Pravir Chandra from the throne in 1961, and he was replaced by his brother.

The failure of the post-independence government to reform

colonial-era policies led to two major post-colonial tribal conflicts in

Bastar, both notable in that they featured the raja and the

adivasis

on one side and the new Indian government on the other. The first

occurred in 1961. After his deposition in that year, Pravir Chandra was

briefly arrested for anti-government activities, which led to the

adivasis

besieging the police station where they believed (incorrectly) he was

being held. For several days Bastar was locked in a state of panic. Huge

protests gripped the kingdom and the new raja, Vijay Chandra, was

unable to quell the disturbance because the

adivasis

refused to accept him as their king. Thirteen protestors were killed in

the ensuing violence. Thousands of signatures were collected to restore

Pravir Chandra to power, and G. B. Pant bemoaned that the ‘Adivasis

still continue to cherish their traditional feelings of respect and

loyalty to the erst-while Princes.’

76

The second major conflict occurred in 1966. On 25 March of

that year Pravir Chandra Bhanj Deo was gunned down by Jagdalpur police

on the steps of his palace. Though the police and the government claimed

that it was the

adivasis that had been

congregating near the palace who had led the revolt, most were in fact

armed only with bows and arrows. A subsequent investigation by Justice

K. L. Pandey also discredited this theory and blamed the police.

77

To this day the so-called ‘police action’ is highly

controversial, and it is widely believed that Pravir Chandra's death was

a political assassination. Though only a small number of

adivasis probably died, rumours still abound that hundreds or even thousands were killed.

78

The

adivasis in the former Bastar State

today continue to venerate Pravir Chandra. Since, 25 March has been

styled ‘Balidaan divas’ or ‘The Day of Sacrifice’.

79

While both the British government and the new Congress government

had a plethora of complaints about one ruler of Bastar after another,

the only group not to complain were their

adivasi subjects.

The continuation of colonial-era policies in Bastar opened

up a political space for the Naxalites. They became an important local

force when they entered the Bastar area in the early 1980s, mobilizing

villagers around their economic grievances—one of their earliest

promises was higher wages for collecting

tendu leaves.

80

Many of the earliest Naxalites came from tribal movements in Andhra

Pradesh, and they began a ‘Go to the village’ campaign in the Bastar

area to enlist tribal support. Two of the main initial recruiting

grounds for the Naxalites in Bastar were hostels and schools, especially

special schools for

adivasis. Youth hostels had

also been an important recruiting ground for communists during the

Telangana mobilization in the 1940s. The two main groups operating in

Bastar now are the Communist Party of India, Marxist-Leninist and the

People's War Group.

From the 1980s to the 2000s, the Naxalites enlisted tribal

support in Bastar by highlighting the failure of development efforts in

the region to improve the lives of

adivasis. On

the surface there appear to be many attempts at reform. In Bastar alone

there is an absurd number of overlapping development organizations: the

Community Development Programme, Community Area Development Programme,

Whole Village Development Programme, Drought Prone Area Programme, Hill

Area Development Programme, Intensive Rural Development Programme,

Tribal Area Development Programme, Intensive Tribal Development

Programme, and the Bastar Development Authority. However, while various

development projects have raised money for the Indian government as well

as private corporations,

adivasis have reaped

few benefits. For example, every year some 50 million rupees is spent on

development schemes in Bastar, but forest and mineral wealth in the

region generates almost 10 times as much for the government.

81

Another example is the Bailadilla iron ore mine in Dantewada, which

is one of the most profitable in India but employs no local

adivasis.

82

By the late 1980s—despite numerous development efforts—only 19 per

cent of the villages in Bastar were electrified, and there was only one

medical dispensary per 25,000 villagers.

83

Similarly, only 2 per cent of land in the entire Bastar region was irrigated.

84

An

Economic and Political Weekly piece on Bastar summarized the situation in 1989:

We have met representatives of almost all of the political parties, in addition to leading advocate [

sic]

and journalists. All of them are of the view that the Naxalite movement

is essentially a socio-economic problem. The failure of development

programmes, exploitation by middle-men and contractors, and corruption

among the officials are the most commonly cited causes. Some of them

even acknowledged the failure of the political parties to effectively

champion the cause of the adivasis.

85

Because development projects have not resulted in a higher standard of living for adivasis

in Bastar, tribal violence has intensified over time. Bastar State is

presently made up of the districts of Bastar, Dantewada (South Bastar),

and Kanker (North Bastar), and from 2005 to 2009 these three districts

experienced a total of 1,171 deaths and injuries from Naxalite violence.

This constitutes 35 per cent of the total number of Naxalite casualties

in India during that time span. Dantewada district alone experienced a

staggering 516 deaths and 472 injuries—it is the single deadliest

Naxalite-affected district in the country. In the end, it is

fitting—considering how little has changed for the tribes of Bastar—that

the name of the main contemporary Naxal front organization in the

region is Adivasi Kisan Mazdoor Sangathan, almost the exact name of

Pravir Chandra's tribal organization formed in 1955.

Conclusion

The rise of the British in India in the eighteenth century led to a number of major adivasi

revolts throughout the country. Colonial officials implemented a number

of policies that aggrieved the native population—in the broadest sense,

they regarded tribals as primitive peoples that needed to be brought

under the control of a modern, centralized state. They took direct

control over and restricted access to forests, thereby displacing

tribals from land over which they had had privileged access for

centuries. While British officials implemented these policies in the

provinces, native princes generally enforced liberal policies towards adivasis, and tribal rebellion was much less severe in the princely states.

After independence, the new Indian government did not

reform many of the colonial-era policies that had led to tribal revolt

in the first place; for example, they continued to exercise complete

control over the country's forests. This, in turn, led to a continuation

of tribal rebellion in the form of the Naxalite movement. This

insurgency, driven mostly by poor adivasis, is still strongest today in areas of former British rule.

Given these two facts—that tribal revolts mostly occurred

in British provinces, and that princely rulers enforced liberal tribal

policies—it is surprising that a major centre of tribal conflict

throughout both the colonial and post-colonial period is the princely

state of Bastar. What accounts for the immense historical conflict in

this small and remote princely kingdom?

Using a wide variety of primary sources, I detailed that

Bastar State experienced extensive British interference during the

colonial period. Colonialism in Bastar led to the implementation of new

forest and landholding policies, the dismissal of several popular rajas

from power, and ultimately the rise of tribal rebellion in the region.

The case of Bastar therefore reaffirms the negative impact of British

rule on India's indigenous communities. While Bastar experienced

extensive colonial interference, it may not have been alone. Recent

historical work suggests that the roots of the Telangana conflict in

Hyderabad State, for example, may also have been due in large part to

British policies imposed on the

nizam.

86

But the case of Bastar also implicates the post-colonial

government in continuing and even exacerbating many colonial-era

policies that had initially led to rebellion—for example, removing

another of Bastar's rajas from power in the early post-independence

period. Furthermore, the socio-economic grievances that originated

during the colonial period have not dissipated in recent years, and

Bastar remains one of the least developed regions of eastern India.

Existing development projects have been beneficial to the state and

private interests, but have done little to assist adivasis

specifically. This explains the rise of Naxalism in the area, which is

only the latest incarnation of a long history of tribal revolt. The

colonial past, therefore, continues to cast a long shadow over the

ongoing tribal rebellion in the vast jungles of the Indian republic.

As British administrators began to colonize other parts of

Asia in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, they took

with them the belief that maintaining some form of indirect rule was

imperative to governing successfully. This was a lesson culled from the

Indian experience. And so colonial officials created the Shan States,

Chin Hills, and Kachin State of ‘Native Burma’ and placed them under

indigenous rulers.

87

In Malaya they likewise created the ‘Unfederated Malay States’ and placed them under the control of sultans.

88

Contemporary conflicts continue to rage in many of these regions—in

modern Myanmar, for example, former areas of indirect rule have seen a

number of ethnic separatist movements since independence.

89

The history of political developments in Bastar State

during colonialism can provide insights into explaining some of these

other conflicts across British colonial Asia. The case of Bastar

foremost prompts a fundamental question: was indirect rule in the

British empire truly indirect, or was it merely a facade hiding the

creeping influence of colonial administrators? If Bastar provides a

preliminary answer, colonialism may be responsible for violence

occurring even beyond the borders of direct rule. And whether the

post-colonial leaders of states like Myanmar and Malaysia have dealt

better with their colonial inheritances than the politicians of modern

India is a question that will go a long way towards determining whether

contemporary violence persists.

British planned famines to kill Indians:-

Can’t

say about rest of India. But in Odisha they were causing one famine

after another, hellbent on culminating a cultural genocide. Why they

wanted to exterminate Odias. Answer is simple, whichever people were

more rebellious and were not easily falling in line were being

exterminated. Odias had in a matter of 50 years rebelled against the

British twice. Hence the extermination and “Famine” was a more

acceptable, publicly defensible way to exterminate a population. Just

ask yourself how often have you heard about jallianwala bagh massacre

and how often the Odisha famine that actually kill...

(more)